Sudanese encounter challenges at the Egyptian border and beyond

Sudanese waiting at Wadi Halfa to cross into Egypt (File photo: RD)

CAIRO –

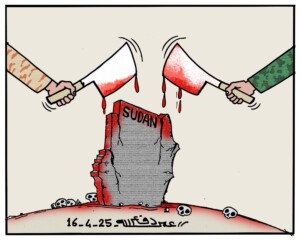

Sudanese fleeing the war in their country to neighbouring Egypt have encountered and are still encountering formidable challenges at the border. Those who managed to obtain an entry visa and other relevant documents are enduring harsh living conditions on the Egyptian side.

Egypt, having received over 250,000 Sudanese refugees since war erupted between the Sudan Armed Forces and the RSF mid-April, is struggling to manage the influx of refugees at its border.

Sudanese refugees are grappling with slow processing procedures and tightened border controls. Tens of thousands, including women, children, the elderly, and people with critical medical needs, find themselves stranded in border towns. They are lacking essential provisions, including food, drinks, and cash.

To enter Egypt, new arrivals are required by Egyptian authorities to possess valid travel documents and entry visas*. Obtaining these necessary documents can take several weeks, leaving many refugees in limbo. Visa rules and allegations of corruption have further impeded their entry, with Sudanese and Egyptian brokers allegedly offering fast-track visas for a fee.

“It is cheaper to pay [the brokers] than stay for months in Port Sudan or Wadi Halfa” said Abdelrahman Ahmed, a recent arrival in Egypt, in an interview by Azza Guergues and Mohamed Amin for The New Humanitarian.

Additional challenges arise from restrictions on the number of buses allowed to cross the border each day, leading to delays and difficulties for refugees. Relatives were separated due to the previous requirement of entry visas for men aged between 16 and 50.

Since June 10, all Sudanese are required to obtain visas , resulting in fewer arrivals and causing significant bottlenecks in places with operational consulates. The fact that temporary travel documents are refused has left many people unable to enter Egypt.

The overwhelmed border towns lack sufficient services, adequate shelter, and an ample supply of food and water. Pharmacies in these areas are running low on crucial medical supplies, including intravenous fluids and insulin, exacerbating the health challenges.

Inside Egypt

With the dire economic situation in Egypt, job prospects for Sudanese refugees are limited. Acquiring a work permit is a complex process, and job opportunities tend to prioritise similarly qualified Egyptians.

Housing is similarly difficult to find, and extremely expensive, causing many Sudanese refugees to live with relatives, volunteers, or share apartments with fellow refugees.

Several Sudanese and Egyptian initiatives are providing support for housing, employment, and legal issues. However, the cost of basic supplies, for instance diapers and formula milk, remains a financial burden for many. International aid organisations offer limited financial assistance, but their reach is insufficient to aid all refugees in need

Compounding the situation, the Egyptian government’s policy not to establishrefugee camps has left international humanitarian groups in Egypt underfunded and constrained. The burden of support falls on local Egyptian and Sudanese community groups, but their resources are limited.

Abdullahi Halakhe, a senior advocate for east and southern Africa at Refugees International, told The New Humanitarian that “if Egypt opts for a no-camp policy, it should, as a matter of course, provide an environment for the refugees to earn a livelihood. Camps are hardly ideal, but at least in camps the refugees get humanitarian assistance.”

Despite this, Egyptian President Abdelfatah El Sisi has adamantly refused the establishment of refugee settlements in the country.

The dire conditions have led some refugees, faced with the worsening situation in Egypt, to decide to return to Sudan, despite the ongoing war. “After staying for two months without a clear source of income, our situation was worsening and we started thinking of going back to Sudan despite the war,” Khartoum resident Muna Alshiekh told The New Humanitarian.

_____________

* In 2004, Egypt and Sudan signed the so-called the Four Freedoms Convention, allowing the free movement of citizens between both “brotherly countries”, as well as working and owning property with no special permit. Soon however, it became clear that Sudanese men between 18 and 50 years old still needed a visa to be able to cross the northern border. In 2018, the authorities in Cairo requested an amendment be made to some of the agreement’s clauses, including officially restricting the entry of Sudanese to Egypt. On June 10, after more than 200,000 Sudanese had sought refuge in Egypt, Cairo decided to oblige all Sudanese to obtain a visa to enter the country.

and then

and then