Celebrating women’s history in Sudan

A woman celebrating the announcement that it will be a criminal act to practice FGM in Sudan in 2020 (Sari Omer)

DABANGA SUDAN – March 31, 2023

By Camille Straatman

Women have played an important role in shaping Sudan’s history and society. Yet, as so common throughout history, their contribution has not always received the recognition it should. As women’s history month draws to a close, Radio Dabanga wants to celebrate the wealth of contributions Sudanese women have made to society, whether it be activist, cultural, or political.

In this feature article, we present you with a small selection from a nearly infinite list.

Everyone who has followed the news in the past years has undoubtedly come across the image of a woman in a traditional Sudanese white thobe (also called tobe or toob, a rectangular piece of fabric that women wrap around their bodies and heads), standing on top of a car in a sea of protesters, leading protest chants.

The woman in the powerful image, Alaa Salah, was called Kandaka online and became a symbol of the revolutionary protests that eventually toppled the dictatorial regime of Omar Al Bashir and specifically of the role that women played in leading the protests.

Kandaka refers to the Nubian Queens of Sudan’s ancient Kingdom of Kush, centred in the Nile valley of southern Egypt and northern Sudan. They were warrior queens that had a great impact on the way the kingdom was run. Symbolising strong women fighters, the term became a synonym for the women revolutionaries who played an important role in the revolution that overthrew the regime of dictator Omar Al Bashir.

Women made up an estimated 70 per cent of these mass demonstrations against the Al Bashir regime and played an important role in organising protests, often taking the form of ‘Marches of the Millions’ and sit-ins. They still play a very active role in Sudan’s resistance committees, grassroots activist groups that have been the driving force behind the pro-democracy street protests during and after the 2019 December Revolution and the 2021 coup.

Recently, the resistance committees in Khartoum state organised a ‘March of the Martyrs’ Mothers’ in conjunction with Mother’s Day to demand the overthrow of the military junta. Three women were arrested by the police and allegedly subjected to verbal abuse by officers who called them ‘prostitutes’.

Against oppression

It is no secret that women, especially activists, have faced significant repression during the Al Bashir dictatorship when strict Sharia laws were enforced, and the present military junta government.

On International Women’s Day, Radio Dabanga reported the situation of women in Sudan, especially in conflict areas, is witnessing a noticeable deterioration in all respects. Especially displaced women suffer from oppression, gender-based violence, and sexual harassment.

Yet, women remain defiant.

The No to Women’s Oppression Initiative, for example, has fought tirelessly against the Public Order Law and the ways in which it was used to oppress women in Sudan.

In an interview with Radio Dabanga, founder Ihsan Fagiri explained that the initiative was formed in 2009 by women intellectuals, lawyers, and scholars to defend women’s rights in Sudan after Lubna El Hussein, a Sudanese journalist working for the UN, was detained alongside 13 other women for wearing trousers in a restaurant in Khartoum.

The fight against oppression and dictatorial regimes far predates the current anti-coup protests, the 2019 December revolution, and activism during the Al Bashir regime. Women also played an important role in the fight against colonialism.

As scholar Mawahib Ahmed Bakr writes, Sudanese historians have documented many cases of Sudanese women who struggled against colonialism “even before the beginning of women’s access to primary formal education in the early twentieth century”.

One example is the story of poet and warrior Mihera Bint Abood, whose father was the leader of the El Shaigiya Tribe in Northern Sudan, the historian explains. “Mihera participated with the knights of her tribe in fighting against the Turko-Egyptian invasion in 1821”.

Another legendary figure is Rabha Alkinaniyya, a simple farmer who played a decisive role in the Mahdist Revolt between 1881 and 1899, where the Mahdist Sudanese waged a war against the Turkish-Egyptian forces and later the British colonial forces, who eventually established the Anglo-Egyptian rule.

Unions

One vehicle that women have used in the fight against oppression is trade unions.

“Historically, the embryo of the women’s movement started to grow after the establishment of the political parties in 1948. The first organised women’s movement started with the establishment of the Union of Sudanese Women Teachers in 1949,” historians Nafisa Ahmed El Amin and Ahmed Abdel Magid write.

They identify the emergence of the Sudanese Women’s union as an important point in history.

In 1952, the first Sudanese woman to be admitted to the Kitchener Medical School, Khalda Zahir Soror El Sadat, and her friend schoolteacher Fatima Talib launched the Sudanese Women’s Union.

Initially, the women started a campaign in their neighbourhood to agitate for the rights of women under British colonialism, but the union became something much bigger, including women from all regional, religious, socio-economic, and ethnic backgrounds in Sudan.

The union booked various successes such as obtaining equal pay for equal work in 1953 and ending Obedience Laws that required women to return to abusive partners and stripped them of other human rights.

Women also make up important shares of teachers’ unions, healthcare workers’ unions, and other professional organisations.

One important women’s group that unionised are Sudan’s tea sellers. These women are a famous part of Sudan’s street life. The food and ‘tea’ (hot beverages) vendors are mainly women, often displaced or migrants from rural areas, and were frequently harassed and prosecuted under the Omar Al Bashir regime.

As recent as four months ago, protests took place against renewed police campaigns against women tea and food sellers in Khartoum. The participants of the vigil called “for an immediate halt to police violence against women vendors in the informal sector and for police officers involved to be brought to trial,” said Awadiya Kuku, chairperson of the All Professions Co-operative Association.

Her colleague Awadiya Abbas, a National Textile Workers Union organiser since 1969 and member of the women’s union until it was dissolved in 1971, founded the Women’s Cooperative Association of Popular Food and Beverage Sellers in 1995 to support Sudan’s tea vendors.

Alongside No to Women’s Oppression Initiative’s Ihsan Fagiri, also a tea seller, Abbas was interviewed for Radio Dabanga’s Inspirational Women series.

She explained how the police used the Public Order Law to attack tea sellers: “To combat the public order law, we held vigils and marches in many localities and met with many officials. Prosecuted by authorities, I arrived at our main office… They attacked us at our office and took our chairs because we resisted their decision to limit our work hours until six o’clock… But we continued to resist.”

‘To combat the public order law, we held vigils and marches in many localities and met with many officials’ – Awadiya Abbas

Many of the women attending the revolutionary 2019 sit-in in front of the Army Command were tea sellers as well. Abbas told Radio Dabanga how she stayed at the sit-in to prepare food and drinks for the activists.

Tea seller Hiliwah told photographer Helena Lea Manhartsberger how she spent her time at the sit-in: “I went to the sit-in because I wanted to support the revolution. I even helped to control the people who entered the camp at the barricades, to make sure nobody brings dangerous objects in. […] I really liked the atmosphere at the sit-in, there wasn’t any single hungry or thirsty soul, and there was tea and food for everyone.”

“In Ramadan, I prepared Zalabia and tea for iftar (breaking the fasting after sunset). At the sit-in, I went from tent to tent and distributed food and tea to the people. I never got back the teapots, but I absolutely don’t care, I lost people in the revolution – who cares about teapots?”

She explained more about the important role of women in the revolution. “In this revolution women had a very important role. They fought and sacrificed themselves to free this country. Most of the protesters were women, a lot of them housewives.

“Not long ago I had a discussion about the problem of public transport with a man in a bus. He asked me: ‘You made this revolution. Why don’t you make another march for better transportation?’ I answered: ‘After we did all this while raising our kids and doing all the work at home it’s your time to support us now’.”

‘After we did all this while raising our kids and doing all the work at home it’s your time to support us now’ – Hiliwah

Justice system

It is not just through anti-oppression campaigns and unions that women have played an important role in reforming Sudan’s legal system, there is a powerful legacy of women transforming the political and justice systems from within.

For Radio Dabanga’s Inspirational Women Series, we interviewed Siham Osman, the first woman to hold the position of Under-Secretary at Sudan’s Ministry of Justice. She has always worked tirelessly to make sure that women’s opinions are taken into consideration in legislation and juridical proceedings and works to bring Sudan back into the international system.

After Osman assumed the role of under-secretary, women in Sudan won several victories in relation to laws and legislation, including the ratification of one of the most famous and controversial international agreements, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW).

Her lengthy career has also seen her become Chairperson of the Committee to Combat Human Trafficking and other influential positions.

Women also make up an important part of the revolutionary Emergency Lawyers, who support protesters since the October 25 military coup, and the Darfur Bar Association (DBA), which have been vocal against the Al Bashir regime and the subsequent military juntas.

This work does not go without its risks.

Nafeesa Hajar, a member of the Emergency Lawyers and Vice President of the DBA, was intimidated last year and received threats if she and her colleagues would continue to provide legal aid to detained protesters and those who were sexually harassed and raped during the December 25 demonstrations.

The DBA said in a statement yesterday that more of its lawyers have been intimidated in the same way. The Sudanese Bar Association (SBA), too, have faced repression.

Other members of the Emergency Lawyers, such as Rehab El Mubarak, have been paramount in the fight for justice and fair court procedures for pro-democracy activists.

Many more women lawyers, such as Eman Hasan, play important roles defending pro-democracy protesters in often unfair trials and inhumane detention conditions where they face human rights abuses.

After a recent trial in which eight Sudanese activists were acquitted of ‘fabricated and malicious’ murder charges, defence lawyer Rana Abdelghaffar told Radio Dabanga that “the charges against active revolutionaries were fabricated to keep them away from the revolutionary movement”.

Politics

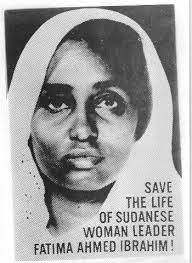

In 1965, Fatima Ahmed Ibrahim became the first woman parliamentarian elected in Sudan as a leading member of the Communist Party of Sudan (CPoS). She was born in 1932 or 1933 in an educated and religious family.

Ibrahim’s political awareness began early, in particular after the British Department of Education forced her father, a teacher, to resign for refusing to teach English. At secondary school, she began campaigning for women’s rights under a pseudonym in a periodical leaflet called El Ra’ida [the woman leader] and in the Sudanese press.

She also played a key role in establishing the Sudanese Women’s Union in 1952. Ibrahim joined the communist party in 1954. Both the Women’s Union and the Communist Party played an important role in the “October 1964 Revolution”, which led to the dissolution of General Abboud’s authoritarian regime.

Despite harassment and the execution of her husband, trade union leader El Shafee Ahmed El Sheikh under President Jaafar Nimeiri in 1971, who also disbanded the women’s union, and a house arrest of two-and-a-half years, Ibrahim continued to work for the rights of women.

For the next two decades, she remained a target of the subsequent authoritarian governments and in 1990 she fled to the UK where she continued her activities until her death.

Women gained the right to vote and run for office, and in the following 1965 general election, Ibrahim was elected a member of the Sudanese parliament and became the first Sudanese parliamentary speaker.

Some other women, such as Maryam El Sadig El Mahdi of the National Umma Party, have played an important role in Sudanese opposition parties for decades. Originally trained as a doctor in both Jordan and the UK, she later received a higher diploma in development and gender issues from Ahfad University for Women and a Bachelor of Law from Neelain University in Sudan.

As the daughter of El Sadig El Mahdi, who was prime minister of Sudan before his government was forced to step down in the 1989 coup by Al Bashir and his Islamist following, Maryam climbed up the party ladder. Like other outspoken politicians, she faced threats, arrests, and imprisonment under the Al Bashir dictatorship.

Since the toppling of the Al Bashir regime, during the transitional government of PM Abdallah Hamdok, women occupied more important positions in government and El Mahdi became the Sudanese Minister of Foreign Affairs.

After the October 2021 coup, the Financial Times listed El Mahdi as one of the 25 most influential women of 2021 and described her “as one of [the military’s] most outspoken critics and as a voice for all the women who took to the streets to campaign for change.”

Journalism

Many human rights abuses and much of the political work done by women would go unnoticed if it was not for the contributions of brave women journalists.

In an interview for International Women’s Day, Sudan’s Journalists Association for Human Rights (JAHR) Coordinator Feisal El Bagir emphasised the great role played by women in Sudan, especially women journalists, in spreading awareness and fighting for the rights to organisation, expression, and gender equality.

El Bagir, however, also explained that women journalists frequently suffer from violations and harassment on the Internet and do not feel safe and that Sudanese women played a major role in the glorious December revolution, but they did not get their share of political influence or recognition.

Four months ago, Radio Dabanga reported on the economic violence women journalists faced in the first lockdown.

Two weeks ago, journalist Ikhlas Nimir announced her intention to sue the Sudanese police for allegedly physically and verbally assaulting her while she was covering the demolition of slums in El Mamoura in eastern Khartoum.

Her reporting work was political: “the police violently removed the slums, ignoring the wailing of the women living there who begged the police forces to allow them to at least take their belongings from the shacks before they would be demolished”.

Culture

Not all political contributions of women come through governance or demonstrations, women have also made enormous contributions to Sudan’s cultural life and promoted women’s rights and democratic rights.

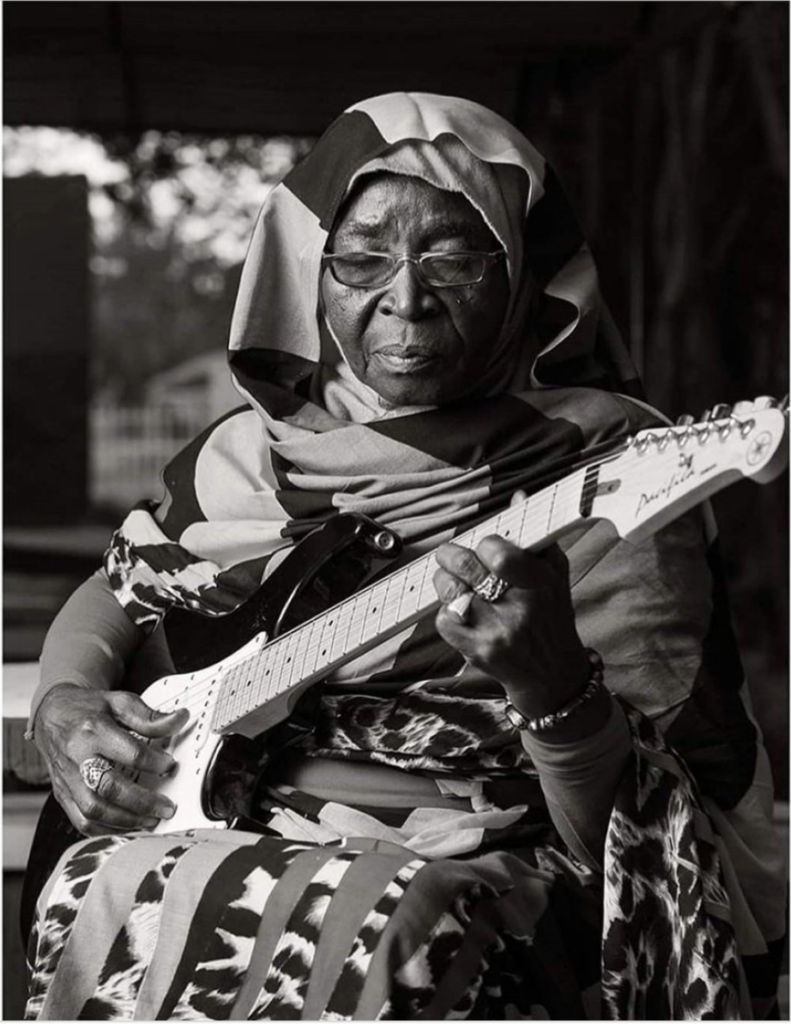

In an interview for Radio Dabanga’s Inspirational Women series, musician Zakia Abu Gassim Abu Bakr talked about her outstanding career. She has received honours from inside and outside Sudan but had to teach herself music as, for women, formal education in music and arts was a narrow path. In her 80s, Zakia is still going strong and formed the all-women band Sawa Sawa.

In the interview, she also spoke about repression and her opinion on the government. She criticised government agencies for neglecting Sudanese art and failing to support its artists on their journey to reach international audiences.

Her husband, ‘king of Sudanese jazz’ Sharhabil Ahmed, once explained that during concerts in the Al Bashir era “the police could arrive at any time with guns and order an artist to step down from the stage. Sometimes they would take our instruments and sound systems or shoot above the crowd with real bullets to try and stop us by force. It felt like the lives of artists were in great danger.”

Novelist and social activist Sara Hamza El Jak Abdallah is another influential figure interviewed by Radio Dabanga. As one of the few successful Sudanese women novelists, she is also the founder of the Faal Cultural Centre which empowers young women through writing and literary education and has always engaged in feminist societal work.

The women characters in Sara El Jak’s novels are always strong and capable, their role in the world is highlighted, their suffering is reflected upon, and their successes are cherished as worthy of appreciation. El Jak writes for the people of Sudan and Sudanese women first and foremost. Yet, the number of Sudanese women novelists is small.

Over the past decades, much literature had to be smuggled into Sudan. The now-ousted Al Bashir regime banned many books and heavily censored the books published. During the revolution in 2019, before the June 3 Massacre took place, banned books were available at the protesters’ informal libraries.

What distinguishes Sara El Jak’s work is that it has found its way to publishers at a time when the majority of literary works face the problem of having no publisher as many of these censorship problems still persist.

Other activism

The fights for democracy, political justice, women’s rights, and workers’ rights are not the only fights women engage in.

Women play an important role in the fight against ethnic discrimination and war and for the protection of the rights of the displaced, such as Nuba Kandaka Safaa Tutu, but also in the struggle for climate justice.

Nisreen El Saim is a climate activist and revolutionary who has been a leading figure in many global and local struggles, ranging from the December Revolution in Sudan to the United Nations climate summit. She warns about the impacts of climate change on Sudan and its displaced.

Of course, this article presents you with a far-from-complete list of inspiring examples. Sudanese farmers, teachers, healthcare workers and many other women all play an important role in the shaping of Sudan and its history.

and then

and then