‘Mediating South Sudan accord is in Sudan’s best interests’

Researchers and strategists in Sudanese affairs said that the resolution of the conflict in South Sudan mediated by Sudan, which produced a power-sharing deal and final security arrangements, has been motivated by reasons of security, economic, and political considerations as a catalyst to enter as an intermediary for peace.

South Sudan rebel leader Riek Machar, President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, Sudanese President Omar Al Bashir, and Salva Kiir, president of South Sudan (SUNA)

South Sudan rebel leader Riek Machar, President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, Sudanese President Omar Al Bashir, and Salva Kiir, president of South Sudan (SUNA)

Researchers and strategists in Sudanese affairs said that the resolution of the conflict in South Sudan mediated by Sudan, which produced a power-sharing deal and final security arrangements, has been motivated by reasons of security, economic, and political considerations as a catalyst to enter as an intermediary for peace.

Dr Suleiman Baldo, senior researcher at the Enough Project, pointed to the economic motive of restoring the flow of the oil of South Sudan, which was disrupted by the war and reflected in the deterioration of Sudan’s revenues from transit fees. This diminished the ability of the government of South Sudan to pay compensation for the transitional agreement agreed upon under the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement with the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), which eventually led to the secession of South Sudan in July 2011.

Baldo said in an interview with Radio Dabanga that the Khartoum regime also has a direct political interest in restoring calm to the situation. “This can also assist to restore the pumping of oil and technical rehabilitation of oil production areas, which constitutes an economic return to Khartoum to improve the deteriorating economic conditions and the need for any sources of foreign currency.”

Positive image

He said that “the Sudan government’s other motive for mediating the conflict is that this role, which ended with the signing of the power-sharing agreement on Sunday, will give Sudan a positive image in the international and regional community on the one hand and restore some aspects of the regional powers as a leading country in the Horn of Africa and East Africa at all levels.”

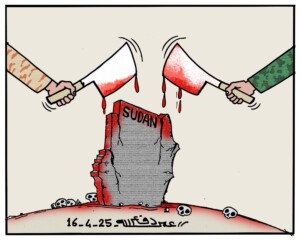

Baldo pointed out that through the role of the mediator, the regime in Khartoum is also seeking to rehabilitate the image of Sudan from a country causing conflicts and unrest to South Sudan into a country that helps in finding solution; “Sudan would like to play a role that ignites the fire and at the same time calls to extinguish it”.

Political dominance

He stressed that “Khartoum has a direct interest in helping to shape the political future of South Sudan in order to ensure its political dominance over the political situation there. Sudan’s seriousness in securing stability and prosperity for South Sudan will not be realised or confirmed unless Khartoum lifts the economic sanctions it has imposed on South Sudan since its independence in 2011 and encourages at the same time to trade between the two countries.”

Baldo highlighted that “despite Khartoum’s repeated promises to open the border crossings and allow trade movement, nothing of that has happened so far. The continued closure of the border means that the mentality that developed ‘Plan B’ in Khartoum is still dominant and shows at the same time that there is a problem in the real intentions of the regime in Khartoum.”

He pointed to a statement by as senior government official that closing the border to trade with South Sudan had caused Khartoum the loss of $5 billion between 2011 and 2014, which means that the average estimates of trade with South Sudan amount to $1 billion a year.

Signing ceremony

According to President Omar El Bashir’s speech at the signing ceremony of the final peace agreement for South Sudan in Khartoum, the pumping of oil will resume on September 1, which could be a significant addition to the two countries, both suffering from inflation the decrease of the national currencies.

Trade balance

Economists say that among the fruits that would benefit Sudan is at least $3 billion in the transport and transit processing fees of $25 per a barrel which, according to the agreements between the two countries an average of $9 to $11 per barrel, this in addition to the $15 compensation for Sudan for cessation to be paid within three years with a total of $3 billion.

Economists also believe that the return from the oil crossing of “$3 billion fee” can cover 70 to 75 per cent of the trade balance whose deficit had amounted to about $4 billion in 2017.

South Sudanese analysts conditioned the success of implementation of the agreement signed between the Government of South Sudan and the opposition movements in Khartoum on Sunday with passing over the bitterness, turn the page personal differences and deal with an open mind among all the parties.

Personal differences

Yesterday journalist and political analyst on issues of the South Sudan, Brian Etibeh, warned in an interview with Radio Dabanga of the impact of personal differences between the president and his five deputies on the implementation of the agreement.

He also pointed out that the issue of the assembly of opposition forces would widen the gap of differences and blow up the agreement if not handled with caution, this as well as the problems of funding expected for the process of troop assembly.

Etibeh said the agreement provided that the rebel fighters of former vice-president Riek Machar’s, Salva Kiir’s main opponent, would not enter Juba and would only be provided with a symbolic group, with UN troops providing personal protection.

United Nations forces

He explained that the imbalance of power and armament between the SPLM forces led by Salva Kiir and United Nations forces indicates the lack of adequate safeguards for the safety of Riek Machar.

Etibeh explained that a faction of the National Salvation Front group led by Thomas Serloo did not sign the agreement because of disagreements over the power sharing in the states and the provisions of the agreement in addressing corruption issues.

He expected a continuation of military confrontations between the government and the forces of Thomas Serloo in the absence of his joining the agreement.

He expressed the hope that the agreement would lead to increased oil production and national income.

He called for laying strict foundations for the employment of oil revenues and directing them to provide services, build roads and infrastructure and provide health and education.

Etibeh stressed the need for the neighbouring countries to monitor the implementation of the agreement, especially with regard to optimal employment of oil revenues for the benefit of citizens rather than to exploit them negatively by corrupt elements.

and then

and then