Judicial rulings: The sword of the Sudanese army is on the necks of civilians

Mustafa El Ghazali, a student of Al-Zaim Al-Azhari University who was sentenced to ten years in prison on charges of collaborating with the Rapid Support Forces (Photo: Al-Zaim Al-Azhari University / Facebook)

By Abdel Moneim Madbou for Sudan Media Forum Joint Editorial Room

Mustafa El Ghazali did not expect that a passing joke he made in a WhatsApp chat with a friend would lead him to a cell and a judicial sentence of ten years in prison. Although he explained during the same conversation that what he said was just a joke, denying any connection to the Rapid Support Forces, his clarification did not intercede for him.

Mustafa, a student at El Zaim El Azhar University, took refuge in Cairo with his family after the outbreak of the war and then returned from there, to work in gold prospecting in the Abu Hamad area in the northern state. Later, he went to Atbara to take his final semester exams at the university. After the exams, and on his way back to the gold mines, the intelligence services stopped him at the Khaliwa checkpoint, where he was arrested and transferred to the court, which issued the harsh sentence against him.

In a similar case, the Bahri court issued a death sentence against a young woman named (Yuwa), a resident of the El Mazad neighbourhood in Bahri. Since the outbreak of the war, Yiwa has been working for the rest of the neighbours, according to the residents of the neighbourhood: she brought water, prepared food, distributed it to neighbours and the elderly, and ran a small kindergarten for children. But this pure biography was turned upside down when she found herself in the dock on charges of “collaborating with the Rapid Support” before she was sentenced to death. Despite the fact that her innocence was confirmed by the residents of the neighbourhood, who see the case as a settling of scores. According to the accounts of the residents, after the liberation of Bahri, Yuwa revealed the involvement of a family known for stealing abandoned houses and the involvement of its sons in the ranks of the Rapid Support. The family, according to residents, used their influence to fabricate accusations against Yua and presented false witnesses to convict her.

These are two of the hundreds of judicial rulings issued after the outbreak of the war on April 15, 2023, and have sparked widespread criticism of the Sudanese judiciary. They indicate that thousands of citizens are languishing in cells for similar reasons, and the two incidents indicate that the catastrophic effects of the war did not stop at killing thousands, displacing millions of Sudanese people, and destroying infrastructure, but went beyond that to the corridors of justice in the country. A few months after the outbreak of the war, Sudanese courts began issuing death sentences Citizens have been sentenced to years in prison for collaborating with the Rapid Support Forces. These sentences are presented as punishment for crimes (undermining the constitutional order, provoking war against the state, and crimes against humanity) but in the eyes of many they are more than courts used as tools of intimidation, repression, and settling scores, rather than as platforms for justice.

A sword on the necks

In recent weeks, the pace of issuing death sentences against civilians on charges of collaborating with the Rapid Support Forces has escalated, and hardly a day or two goes by without the courts issuing decisions to order the execution of citizens in trials that lack the minimum standards of justice, according to human rights experts. Lawyer Mohamed Salah, a member of the Emergency Lawyers Group, confirms in an interview According to Radio Dabanga, the judicial system in Sudan has turned into a political tool in the hands of the army, which is used to terrorise civilians, support its orientations in the conflict, and create a state of fear and apprehension within society.

He believes that the ongoing trials lack the most basic standards of legal integrity, and that the charges against them, especially the charge of “collaborating with the Rapid Support”, are not based on a legal or constitutional basis, and that the trials are now being conducted with improper legal procedures. He stressed that what is happening is a complete politicisation of the judiciary and turning it into a security arm of the army, through false accusations and illegal measures, aimed at humiliating civilians and pushing them to accuse each other, in a context that serves the interests of the security services, especially in Port Sudan and other areas.

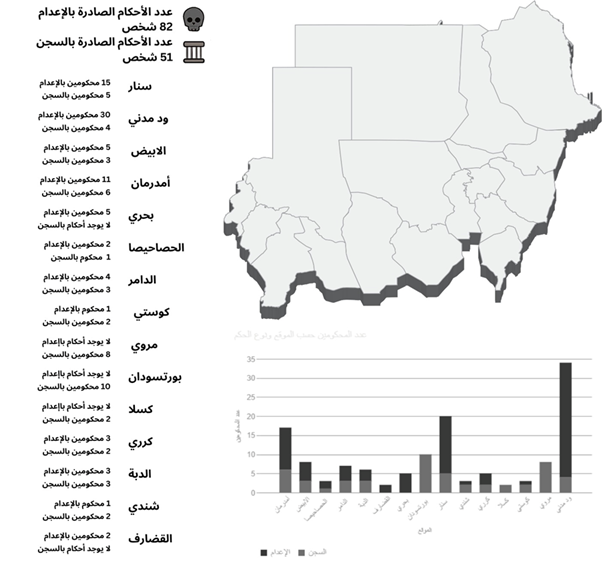

From June 1 to July 31, 2025, Radio Dabanga monitored 82 death sentences and 51 prison sentences ranging from life to five years, issued by the courts in the states controlled by the armed forces and published on the official website of the Sudan News Agency. As shown in the diagram below…

Politically, lawyer Mohamed Abdel Moneim (El Sulaimi) believes that these sentences reflect the army’s tendency to use the judiciary as a tool in its battle against its opponents, specifically to legitimise repressive practices that contradict international humanitarian law. These sentences aim to spread terror in societies and send political messages to the opposition that the cost of cooperation with the RSF will be death. In an interview with Radio Dabanga, El Sulaimi asserts that the majority of trials are taking place away from the eyes of the media and human rights monitoring and are not covered by the media. They are not monitored by organisations that claim to monitor human rights violations. As a result, news of trials only reaches when the accused is a well-known figure, or when his or her family has the ability to bring the case to the public. This obfuscation makes any attempts to enumerate cases or document violations mere speculation. Through ongoing legal monitoring, El Sulaimi says that the conviction rate in public cases reaches 99.9 per cent, which raises serious doubts about the availability of the conditions of justice and the integrity of the proceedings.

He stated that the vast majority of the defendants belong to specific political currents or ethnic backgrounds. “There is a clear pattern of targeting,” he adds, as either the accused is a politician associated with the Forces of Freedom and Change parties, or a citizen of western Sudan who belongs to an ethnic group that is seen as a social incubator for the Rapid Support Forces. “There is a list broadcast by Sudan TV of 35 people from the city of Nyala as wanted on charges of money laundering and collaborating with the Rapid Support Forces, some of whom died more than ten years ago, and others are elders Elderly people who left Sudan a long time ago… You can imagine the magnitude of the paradox.”

The list of people fugitives from justice on charges of collaborating with the Rapid Support Forces, issued by the Public Prosecution in May 2025 and broadcast by Sudan National Television.

Judicial Proceedings

According to international humanitarian law, trials in conflict zones in general must be subject to the conditions of a fair trial, with procedural guarantees for the accused or defendant, or for the parties to the case, so that there are legal procedures in the processes (arrest, investigation or investigation, and referral to the court), and there are supposed to be guarantees in terms of legislation and law that the accused will be tried by natural law and will not be subjected to any arbitrary procedures, or any procedures that digest his right to be brought to a fair trial, and he is not entitled to A civilian shall be tried before a military judge or a military court. There must be institutional guarantees that there are institutions that meet the conditions of a fair trial (a court of first instance, a court of appeal, a Supreme Court, and a constitutional court), and if these courts are not available, the trial becomes unfair and constitutes a violation of international humanitarian law.

Legal basis

Mohamed Salah, a member of the emergency lawyer, believes that the charge against the defendants of cooperating with the Rapid Support has no legal basis, and added, “Even the charge of cooperation with the Rapid Support has no legal or constitutional basis, considering that the Rapid Support Forces, according to the decisions of its establishment during the era of the Salvation Regime, are a regular force, in addition to the decisions of El Burhan himself confirming that they are part of the armed forces.” Lawyer

Mohamed Salah confirms to Radio Dabanga that the judicial system in Sudan has turned into a political tool in the hands of the army, used to terrorise civilians, support its orientations in the conflict, and create a state of fear and apprehension within society. He argues that the ongoing trials lack the most basic standards of legal integrity and that the charges against him, in particular the charge of “collaborating with the Rapid Support”, have no legal or constitutional basis.

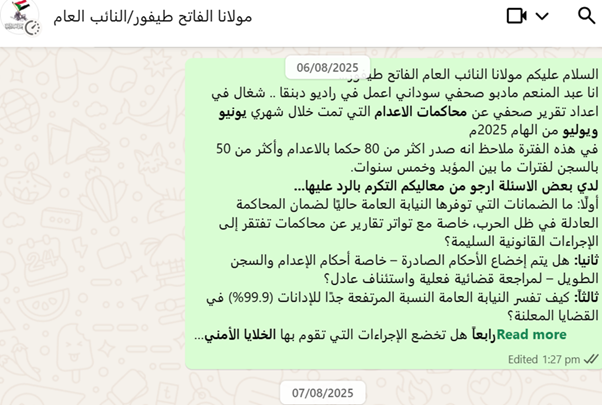

Radio Dabanga tried to contact the Sudanese Attorney General, Mr. Fatih Tayfour, to answer the questions, but he did not respond, as shown in the screenshot below

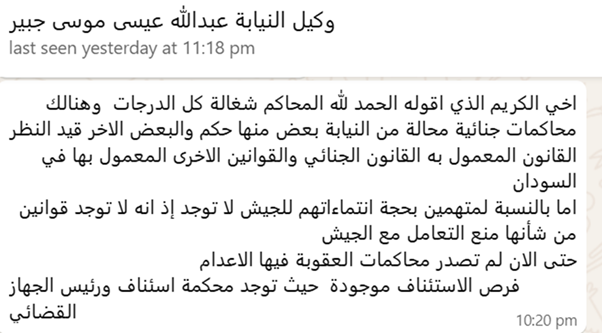

The prosecutor of South Darfur state, Abdullah Issa Jubeir, which is under the control of the Rapid Support Forces, responded to the question of whether there are trials taking place in Nyala on charges related to cooperation with the armed forces, telling Radio Dabanga, “There is no legal article that prevents dealing with the armed forces, and the courts in Nyala operate according to the Sudanese criminal law, and have not issued a death sentence.”

Trials in absentia and selective

In the context of trials related to abuses during the war, the Port Sudan court, headed by Judge Mamoun El Khawad, charged 16 RSF commanders, most notably the commander of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), with war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, most notably the commander of the forces, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo. On the other hand, the judiciary is facing sharp criticism from observers over what they described as “selective justice”, after it overlooked the prosecution of a number of military and political leaders and former fighters in the ranks of the RSF, including the commander of the Sudan Shield, Abu Akleh Kikel, in addition to figures who appeared in press conferences in Port Sudan in which they announced their return from the ranks of the Rapid Support Forces as advisors to Commander Hemedti. At the same time, unarmed civilians who were unable to leave the areas entered by the RSF are being charged with collaborating with the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), some of whom face death sentences or life imprisonment.

Lawyers under pressure… Trials without guarantees

This reality raises legitimate questions in light of the lack of guarantees of a fair trial: Do the defendants get their full legal rights? Is the judiciary used as a cover for political and racial revenge? Here, a lawyer who pleaded in one of the cases in which his client was accused of collaborating with the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) said that the trial that took place lasted only two sessions, and that he was not given enough time for the defence. Some courts have lawyers to defend the defendants, but Lawyer Sulaimi points to ongoing harassment by the security services. The most recent of these was the arrest in Port Sudan of lawyer Muntaser Abdullah, who was defending political prisoners. Many trials were conducted on a summary basis, and there were cases of field trials that lacked minimum standards of justice. He adds that some defendants remain in detention for long periods of time before being brought to trial, making the period of imprisonment a punishment in its own right, even if the court later acquits them. The Appeals Chambers also delay significantly in issuing their decisions, leaving the fate of convicts in the dark for long periods.

Meanwhile, Mohamed Salah, a member of the emergency lawyer, revealed that the judicial procedures are flawed, as trials are often held without the presence of lawyers, similar to the public order courts during the Bashir era, and the charge turns into a tool for settling personal scores, whether by the authorities or even other civilians. Civilians who lived in the areas controlled by the RSF, and were forced to deal with it de facto, find themselves accused of collaborating with it, although this does not amount to a crime. Lawyer Mohamed Salah pointed out that Hundreds of civilians are in prisons in Port Sudan, Gedaref, and Khartoum, including women sentenced to death or life in prison. Although some lawyers have succeeded in acquitting defendants, trials continue daily, especially in the Karri court in Omdurman, in cases that Salah describes as “an attempt to subjugate civilians and break their will.”

Security Cell

Through Radio Dabanga’s tracking of the arrest procedures of the defendants, what was called the “Security Cell” appeared in some states, which began to be formed in May 2024, after the approval of the Chairman of the Sovereignty Council, Lieutenant General Abdel Fattah El Burhan, and it includes elements of Military Intelligence, the Security Agency, the Police, and the Popular Resistance, and the Security Cell was entrusted with the tasks of working as an early warning device, monitoring sleeper cells, investigating and monitoring suspected persons, places, and activities, searching and raiding sites where hostile activity was confirmed, and joint interrogation for those arrested, and referring cases that require traditional (long-term) security work to the regular agencies, for example (the movement of community incubators from the enemy’s areas to the areas under the control of the armed forces). Through the last paragraph of the tasks, the security cell has become targeting those coming from areas controlled by the Rapid Support Forces, and it is the one that carries out the process of arresting and filing a case against the accused and interrogating him. Lawyer El Sulaimi described this security cell as an immediate military court, which issues and executes judgments directly, adding, “It is a model similar to military courts, the difference is that the security cell is not all army soldiers, including a security apparatus, the Browns, and the Sudan Shield.”

Radio Dabanga contacted six families of the detainees, all of whom refused to talk about the conditions of their sons’ detention, except for the family of student Mustafa. The families justified their refusal by saying that speaking to the media might expose them to harassment by the security services, while a source close to one of the families whose son was arrested more than 7 months ago in one of the central provinces said that their son was not brought to trial and were not allowed to visit him, and they were threatened that if they spoke to the media, their son’s fate would be death.

Salah blamed the army’s security cell for detaining civilians in illegal detention centres, where they are tortured, beaten, and starved before being handed over to the police and charged. Some detainees are held for long periods of up to a year, in places such as the Mount Surkab detention centre, while others remain missing for unknown periods of time, with their families not knowing whether they are alive or dead.

Some detainees are thrown into the streets after torture, especially if their mental state deteriorates, while others remain in secret detention. This harsh reality has led some families to prefer bringing their relatives to court rather than keeping them in the circle of enforced disappearances, at least to know their fate.

Thousands in Cells

In the absence of any transparent government or judicial statements, the number of those arrested on charges related to collaborating with the Rapid Support Forces or provoking war against the state remains unknown. However, local media quoted the Commission of Inquiry into Violations and Crimes Committed by the Rapid Support Forces – formed by the head of the Sovereignty Council and Commander-in-Chief of the Army Abdel Fattah Ibrahan in August 2024 – as saying that it “recorded more than 15,000 accusations against collaborators with the Rapid Support Forces, or informants and participants with it.” In March 2025, the Public Prosecution stated that it had begun the trial of more than 950 defendants in cooperation with the Rapid Support Forces in Gezira State.

According to lawyer Mohamed Abdel Moneim (Slimi), some estimates indicate that there have been more than 5,000 detainees in prisons in Gezira state alone, since the armed forces took control of the state. “And that’s a priest,” he comments, referring to the fact that the total numbers could be much higher across the country. These findings are bolstered by the emergency lawyers’ group, which indicates that there are thousands of detainees in cells in the cities of Khartoum and Wad Madani who face charges that carry the death penalty without availability They have the guarantees of a fair trial. A member of the Executive Office of the Emergency Lawyer said that what is left of the country’s judiciary has become a fully politicised body that implements the agenda of the armed forces, adding, “This is a catastrophic humanitarian and human rights situation that civilians in Sudan are living in.”

Human Rights Organisations Concern The use of the judiciary in the context of the war in the country has become a matter of wide concern for human rights organisations, who see the issuance of death sentences in light of the war and the absence of minimum legal conditions as a clear violation of international conventions, especially the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which obliges states to ensure a fair trial even in cases of emergency. The harsh sentences, including death sentences, on charges of collaborating with the RSF, raise serious concerns about ensuring fair trials, he said, noting that he called on the authorities to review these sentences and halt the execution of death orders. However, Nuwaiser’s remarks angered Justice Minister Abdullah Derf and responded, “Talking about violations or unfair trials without detailed information is unacceptable to the Sudanese government,” and even went further by informing the UN expert of the government’s desire to end the mission in Sudan.

and then

and then