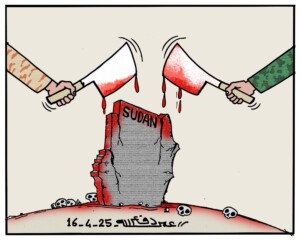

Sudan Transparency and Policy Tracker: ‘What Happens in Darfur Doesn’t Stay in Darfur’

The wave of recent violence in West Darfur has left many shocked observers asking: who was involved in the mass atrocities that occurred, and what are the drivers of the violence and its root causes? In what ways does the violence relate to the October 2020 Juba Peace Agreement that should have brought peace to Darfur and other conflict areas in Sudan but is obviously failing to do so? Finally, what does the violence mean for the junta and the relationships between the different components?

Displaced children in West Darfur (Photo: Enaam Alnour)

Displaced children in West Darfur (Photo: Enaam Alnour)

By Dr Suliman Baldo

The wave of recent violence in West Darfur has left many shocked observers asking: who was involved in the mass atrocities that occurred, and what are the drivers of the violence and its root causes? In what ways does the violence relate to the October 2020 Juba Peace Agreement that should have brought peace to Darfur and other conflict areas in Sudan but is obviously failing to do so? Finally, what does the violence mean for the junta and the relationships between the different components?

In its inaugural policy brief, What Happens in Darfur Doesn’t Stay in Darfur by respected Sudan conflict resolution analyst, Dr Suliman Baldo, the recently established Sudan Transparency and Policy Tracker (STPT) attempts to provide elements of answers to these questions, with the aim of encouraging informed policy decisions both at home and internationally on approaches to bring about stability and sustainable peace to Darfur and to Sudan.

The brief laments: “Yet another week of bloodletting has left West Darfur and the rest of Sudan in deep shock. Attacks on the town of Kereinik and some sixteen villages surrounding it on Friday 22 and Sunday 24 April by militiamen left nearly 200 civilians dead and scores seriously injured and led to the displacement of an estimated 85,000 to 115,000 people. The attackers looted valuables, burned homes and markets to the ground, and destroyed infrastructure essential to civilians such as the local hospital and its pharmacy. Scores of women, children, teachers, and health workers were among those killed. On Sunday 24 and the following days, the violence spread to El-Geneina, the capital of the state, forcing thousands of residents to flee their homes.

‘The pogrom in Kereinik exposed the complicity or incompetence of local security agencies…’

“Beyond what the pogrom in Kereinik and its area revealed about how fraught ethnic relationships remain in greater Darfur, it exposed the complicity or incompetence of local security agencies as some in their ranks joined their ethnic kin during the attack and others failed to intervene due mainly to their lack of military capacity to confront the number of attackers. It is arguable that the formal state security forces can longer be viewed as professionals with a sense of responsibility and neutrality, but rather a part of the ethnic fabric of the conflict. Worse, they are using their formal status as a façade to legitimize their actions.”

‘Ripples beyond Darfur’

Dr Baldo points out that “beyond Darfur, ripples of the deadly events have shed a harsh light on the national scene. The incident added to existing evidence of the fragility of the opportunistic alliance behind the October 2021 coup among the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF), the rival parallel army that the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have become, and armed movements signatory to the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement (JPA). With no credible political base supporting their claim to power, the coup leaders revived a cohort of loyalists of the former regime of deposed president Omar al-Bashir who remained hopeful of returning to power. The generals, who claimed they had a national duty to prevent Sudan’s breakdown and improve its security when they overthrew the civilian-led transitional government, were exposed as incapable of assuming their responsibilities to protect their citizens’ right to life.

‘The Darfur movements who tied their political fate to the coup were shown to be incapable of influencing events in the region…’

Worse, the Darfur movements who tied their political fate to the coup were shown to be incapable of influencing events in the region beyond condemnations of the regular forces’ inability or reluctance to protect civilians and secure the peace.

Dr Baldo also highlights: “Most of the 200 killed in the attacks on Kereinik belonged to the Masalit ethnic group and others settled with them from the Tama, Bargo and Arab minority groups, many of them displaced from earlier phases of the conflict in West Darfur since 2003. The media and eyewitnesses interviewed by STPT described the attackers as herders of Arab descent backed up by RSF soldiers.”

Policies That Kill

At the root of recent violence in West Darfur is the longstanding competition among local communities over access to resources. Previously such conflict revolved around water and pasture but more recently, competing traditional ownership claims on areas believed or known to have gold or oil reserves have emerged as an added driver of violence.

In the conclusion of the brief, Dr Baldo presents the STPT’s recommendations to the government, the political opposition, the signatories of the Juba Peace Agreement, and the international community.

Read complete brief here (PDF)

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the contributing media and/or author and do not necessarily reflect the position of Radio Dabanga.

Dr Suliman Baldo is a widely recognised expert on conflict resolution, emergency relief, development and human rights in Africa and on international advocacy related to these issues. He has worked extensively in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Sudan and travelled throughout the rest of the African continent. In the 1980s and early 1990s, he worked as a lecturer at the University of Khartoum and as a field director for Oxfam America, covering Sudan and the Horn of Africa.

Later, he was the founder and director of Al-Fanar Centre for Development Services in Khartoum, Sudan. He also spent seven years at Human Rights Watch as a senior researcher in the organisation’s Africa division. Most recently, he worked as a senior analyst before becoming the director of the Africa program at the International Crisis Group and at the International Centre for Transitional Justice.

Dr Baldo holds a Ph.D. in comparative literature (1982) and a master’s degree in modern literature (1976), both from the University of Dijon in France. He also holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Khartoum in Sudan

and then

and then