Op-ed: Sudan’s revolution one year after fall of Al Bashir dictatorship

The streets running from Sudan’s army headquarters to the University of Khartoum are quiet this week – shut down by order of the transitional government to stave off the worst effects of the incoming coronavirus.

An iconic moment of the Sudanese revolution as the 'Freedom Train' arrives in Khartoum from Atbara in August 2019 (RD)

An iconic moment of the Sudanese revolution as the 'Freedom Train' arrives in Khartoum from Atbara in August 2019 (RD)

The streets running from Sudan’s army headquarters to the University of Khartoum are quiet this week – shut down by order of the transitional government to stave off the worst effects of the incoming coronavirus.

It is a profoundly anti-climactic departure from the scene a year ago that witnessed young and old, students and professionals, Arab and African peacefully assembled – more than 1 million strong – demanding a new Sudan built upon the revolutionary ideals of “freedom, peace, and justice.”

The regime of Omar Al Bashir had commanded power for 30 years and its military and paramilitary forces were once again fanned out around the city last April preparing to yet again prolong the autocrat’s rule. But on this day, as the protesters stared into Bashir’s abyss of violence and oppression, they did not blink.

Sensing the protesters’ resolve, military and intelligence forces, for so long loyal to the aging dictator, stepped in and removed him from power unleashing a chain of largely peaceful events that for the first time in more than a generation has allowed Sudanese to contemplate what a new Sudan might resemble once freed from the fear, division, and isolation imposed upon them by its own rulers.

In the year since, many hopes have been realized. A charismatic technocrat, Abdallah Hamdok, very much the anti-Bashir, was plucked from UN bureaucratic obscurity to lead the country’s new civilian cabinet. He brought with him similarly-inclined reformers, many from Sudan’s talented diaspora, bent upon providing their countrymen the kinds of opportunities and freedoms that they benefited from in exile.

And they have.

Many of Sudan’s most draconian laws limiting freedoms around assembly, press, and religious worship have been removed. Political prisoners have been released from jail cells, houses of worship have reopened, and no longer must the country’s intellectuals and women look over their shoulders fearing plainclothes military intelligence or religious police.

Heralding Sudan’s return to the international fold, its civilian leaders have been fêted in capitals around the world – unlocking new financial pledges from Europeans, re-establishing diplomatic ties with the United States, and restoring relations with former foes like Israel.

Sudan is also making amends for its predecessor’s past transgressions by settling terrorism related lawsuits with the American families of the USS Cole and, soon, the US Embassy Africa bombings.

But the more things change, the more they have also stayed the same – and gotten worse. The economic crisis that first sparked the people’s uprising in December 2018 has only deepened under the transition to civilian rule.

An ambitious economic reform plan, outlined last November, would have removed subsidies on basic commodities like fuel and wheat, raised taxes, and sold off military-owned companies – generating revenues to fund basic social services and reviving crumbling government ministries.

But the plan has gone unimplemented by the new crop of civilian technocrats who are now accused of lacking both the acumen to enlist broad political support for painful reforms and the courage to upset the military’s entrenched financial interests.

As a result, Sudan’s informal exchange rate is today double what it was when Bashir was toppled, inflation now tops 70 per cent, and household incomes are plummeting – all this as the Government is forced to redirect its limited resources toward fighting an impending coronavirus outbreak.

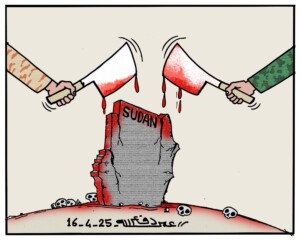

Meanwhile, efforts to dismantle the former regime are also not proceeding as quickly as many in the revolution had hoped and even died for. The successor to the notorious Janjaweed militia, the Rapid Support Forces, has only further entrenched itself into Sudan’s ruling authority. Its leader, Mohammed “Hemeti” Dagalo, implicated in war crimes and crimes against humanity for carrying out Bashir’s orders in Darfur, now serves as Deputy on the country’s ruling transitional Sovereignty Council.

Hemeti’s more-than-prominent role in leading the government’s negotiations to end Sudan’s internal conflicts, his chairing a committee to dismantle the remnants of the previous regime, and now, deploying his personal forces as the frontline in responding to the corona virus, have many international observers worried that in expunging his past record of abuse he is positioning himself as heir apparent at the end of Sudan’s 39-month transition in 2022.

Regrettably, this potential has had a dampening effect on Washington’s support to the new government-fearing that the lifting of remaining sanctions and the State Sponsor of Terror designation could end up depriving Washington of critical leverage down the road should civilian efforts fail or the military retake absolute control.

But despite these headwinds, the Prime Minister’s support from the masses of Sudanese appears seemingly, and improbably, inviolate – so fresh are the recollections of what the alternative to civilian rule resembles.

On this year anniversary of the fall of the Bashir regime, Sudan’s civilian leaders stand as the embodiment of the revolution and the hope that Sudan will one day soon emerge from its military dominance and international isolation.

Undermining them now would be to undermine the revolution itself – something no element in the country seems powerful enough to do – for fear that a million Sudanese might once again take to the streets. Going forward, this threat remains the greatest assurance that Sudan’s transition remains on track.

* This article, reposted here by permission of the author.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the contributing author or media and do not necessarily reflect the position of Radio Dabanga.

Cameron Hudson is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center. Previously, he served as the chief of staff to the US special envoy to Sudan and as director of African affairs at the National Security Council.

Cameron Hudson is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center. Previously, he served as the chief of staff to the US special envoy to Sudan and as director of African affairs at the National Security Council.

Radio Dabanga’s editorial independence means that we can continue to provide factual updates about political developments to Sudanese and international actors, educate people about how to avoid outbreaks of infectious diseases, and provide a window to the world for those in all corners of Sudan. Support Radio Dabanga for as little as €2.50, the equivalent of a cup of coffee.

and then

and then