December revolution: 5 long years for the Sudanese

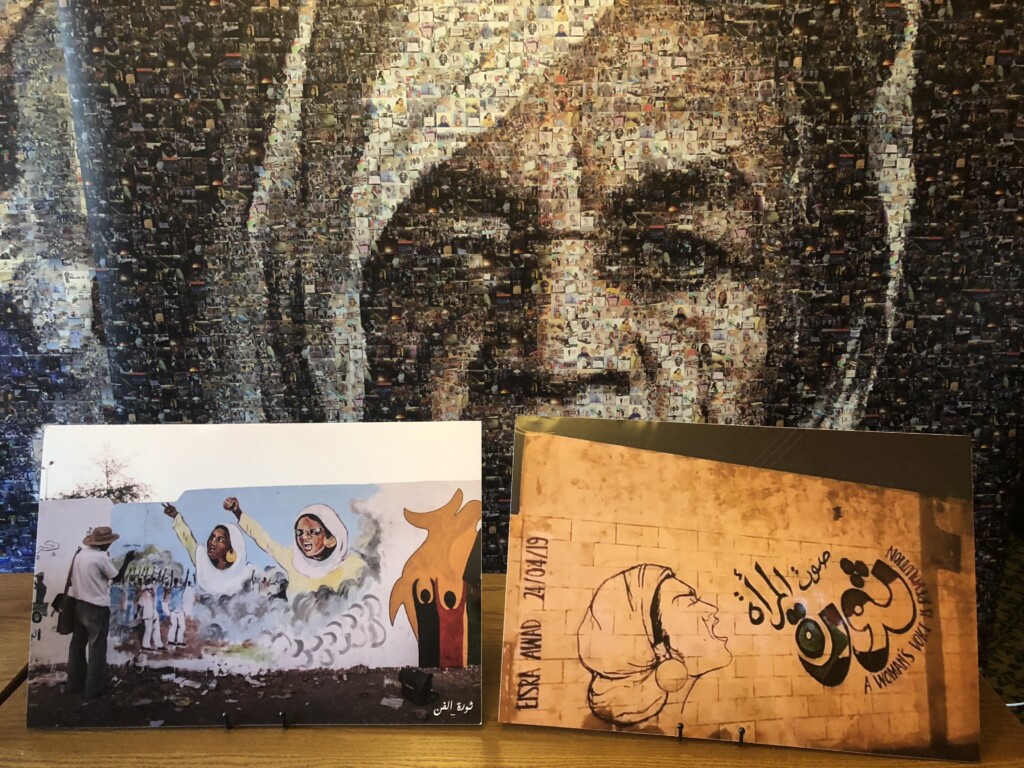

Exhibition of murals and a photo mosaic about the Sudanese revolution (Photo: Social media)

Today marks the fifth anniversary of the December revolution, which resulted in the ouster of former President Omar Al Bashir on April 11, 2019.

September 19, 2018, was a defining moment for the start of the revolution when the first large protests against the Al Bashir regime (1989-2019) in Atbara, Rive Nile state, began. Protests against soaring food prices that erupted in Ed Damazin, capital of Blue Nile region, a few days earlier, signalled the beginning of mass demonstrations against the 30-year reign of dictator Al Bashir.

The spokesperson for the Forces for Freedom and Change-Abroad (FFC-A), and the leader of the Federal Assembly political party, Ammar Hamouda, said in an interview with Radio Dabanga correspondent Omar Abdelaziz yesterday that revolution is a cumulative act. “Revolutions are attributed to the act of change, so I see burning the office of the National Congress Party [established by Al Bashir] in Atbara on December 19 as a political message, turning over a new page.”

“Therefore, this moment deserves to be named as the December revolution without prejudice to the rest of the days, martyrs, and places,” he continued.

Regardless of the disagreement over the date of the start of the revolution, today represents five long years for the Sudanese, who have witnessed major events in its aftermath. The include the joint coup d’état by the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in October 2021 and the war between the two military institutions that erupted on April 15.

Can it be said that the December revolution has failed to achieve its goals so far?

In response to this question, Hamouda described the December revolution as “the manifestation of a very long struggle.” Therefore, judging it depends on the new constitutional systems that spring up in its wake, “even after a long time,” Hamouda teold Abdelaziz.

“The December revolution was intercepted by the military side, which froze its course. Following the October 25 coup d’état many opposed to the FFC, especially Islamists, believed that the FFC members bore a large part of the responsibility for the failure of the December revolution.

State building

Regarding the responsibility of the FFC, Hamouda told Radio Dabanga that “the FFC is destined to lead the revolution and lead the transition”.

“After revolutions, there must be state building,” he said.

Many supporters of radical change, or those who have come to be called “radicals” in Sudan, blame the FFC for having accepted partnership with the army and signing the Constitutional Document in August 2019, after which the new PM, Abdallah Hamdok, could form a civilian-led government, which was suspended by the 2021 military coup. Prominent Sudanese writer, academic, and civil society activist Bagir El Afifi for instance said on Sunday’s Dabanga YouTube page, that there has never been a need to partner with the army.

Hamouda responded to these statements by saying that “it is better to have written charters instead of violence,” referring to the Constitutional Document signed by the FFC with the army and the RSF.

“Neutralising the military and keeping away from weapons is what made the December revolution a success, but when we talk about the task of transition and then going to a democratic state, there must be a written definition of the status of the military institutions,” he said. “This partnership [with the military] is a kind of bridging reality to reach a normal situation, meaning that each party performs its main mission, the soldiers are soldiers, and the politicians are politicians,” he concluded.

Great challenges

The fifth anniversary of the December revolution coincides with the expansion of the war into El Gezira state in recent days.

The FFC-Central Council, including members abroad, and several other political forces and civil society organisations announced in October the formation of the Democratic Civil Forces (Tagaddum) to end the war and re-establish the Sudanese state.

Hamouda believes that there are “great challenges [to the course of the December revolution] that will arise after the end of the war, including disengaging political and military actors”.

Some have become sceptical about the ability of the political field to “provide quick solutions,” he said, stressing that “patience in building political institutions is the best way because quick alternatives may not produce results and may only take us halfway.”

The FFC-CC is now preparing to form what he described as a large civil coordination “for the forces of the revolution or for those civil forces wishing for a democratic transition.”

Resistance committees

In August 2022, the FFC-CC reasserted its desire to work with the resistance committees but was not clear if the contents of the two political charters issued by the resistance committees of Wad Madani in El Gezira and of Khartoum earlier this year will be taken into consideration as well. The resistance committees in Wad Madani launched the Revolutionary Charter for People’s Power (RCPP) in mid-January whilst the Khartoum resistance committees proposed the Charter for the Establishment of the People’s Authority (CEPA) in late February and signed it mid-may. Late 2020, representatives of resistance committees withdrew from a meeting with the FFC-CC about the distribution of seats in parliament, citing disagreements on the agenda.

Yet, the grievances also seemed to concern feelings of exclusion. Young members of resistance committees in Khartoum state told Radio Dabanga at the time that they did not agree with the allocation of seats of the Legislative Council proposed by the FFC-CC.

“The largest percentage goes to the FFC, and they do not represent youth like us in the resistance committees, women, and the members of the armed struggle movements,” a young activist commented.

In its modern history, Sudan witnessed two other revolutions before the December revolution, namely the October 1964 revolution and April 1985 intifada. Both ended in a military coup a few years after their establishment.

and then

and then