Security expert: ‘Sudan becoming world’s largest hotbed of terrorism and violent extremism’

Maj Gen (Police) (Retd) Dr Essam Abbas information technology and data analysis consultant (Photo: Radio Dabanga)

As the devastating war in Sudan enters its third year, the situation still appears to be the same, and it has exceeded the boundaries of the battlefield battles between the warring parties. The devastation that has affected state institutions has not been limited to the battlefronts, but has ignited racist fires (tribal, ethnic and regional) that have reached the level of genocide, according to Washington, and identity killings, hate speech, war crimes and crimes against humanity, which led to the destruction of the social fabric of Sudanese society, and opened the door wide to the dangers and threats of terrorism, violent extremism, the collapse of the state, fragmentation and division.

In an extensive interview on the Radio Dabanga programme Plain Speaking broadcast over the weekend, in a comprehensive episode entitled “The Possibilities and Opportunities of Sudan Becoming a Hotbed of Terrorism and Violent Extremism during the current war”, Maj Gen (Police) (Retd) and now IT and data analysis consultant, Dr Essam Abbas warns that Sudan is moving at an accelerated pace towards becoming a “hotbed of terrorism and violent extremism” if the war does not stop immediately, and urgent measures are taken to rebuild the Sudanese state on new foundations .

He explains that the political turmoil and the control of the “Islamic extremists” in power for three decades from 1989 until the fall of their regime, and their entry into the current war with all their weight and at the forefront, in addition to their very extensive relations with extremist Islamic groups, clearly indicate that Sudan is on its way – if we do not remedy it now – to become the largest focus of terrorism and violent extremism and threaten international peace and security.

The state’s failure to resolve the deteriorating political and economic situation and the outbreak of war has contributed to providing a fertile environment for extremist groups’ activity, he says.

The impossibility of a military solution

At the beginning of the interview, Abbas says that it is impossible to resolve the war, which has turned into an unprecedented humanitarian catastrophe, and adds: “The passage of more than two years since the war proves the impossibility of resolving it by military force.”

He explains that the features of control and progress on the ground are witnessing a continuous change between the army and the Rapid Support Forces, as the beginning of the war witnessed a wide advance of the Rapid Support, before the army was later able to regain the initiative and extend its control over vital areas, most notably Khartoum State, the centre of governance and politics, and El Gezira state, which is one of the largest states in terms of the Sudanese economy.

Battlefield situation Abbas says: “Military operations in Darfur have been disturbingly active, as a result of the insistence of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) to overthrow the city of El Fasher by force, in light of the desperate defence of the army and the joint force allied with it, to prevent the fall of the city.” The three states of Kordofan are also witnessing escalating military operations: in North Kordofan, violent clashes took place in Bara, El Khoy, and the vicinity of the city of El Obeid, while in West Kordofan, the battles were concentrated on the areas of En Nahud and the oil fields near the city of Babanusa. As for South Kordofan, intensive attempts were made to overthrow the city of Kadugli, with the escalation of operations in the city of Debibat.

Entry of missiles and warplanes

Abbas points out that the two parties have made progress on the ground in different areas, but the most prominent feature of the military operations in recent months is the extensive use of drones by both sides. The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) were able to launch attacks, which reached deep into the areas controlled by the army, while the Sudanese Air Force and drones intensified their strikes on the Rapid Support positions. He considers that this qualitative shift in the war represents an influential military development, but it was reflected first and foremost on civilians.

The ongoing military movement has left many innocent victims “who have no choice but to fight this war,” he says, in addition to the widespread destruction of infrastructure in various areas, whether under the control of the army or the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Places of worship, hospitals and markets have also not been spared from the targeting, citing documented incidents such as the bombing of a mosque in El Fasher that killed dozens of worshippers, as well as attacks on hospitals and other vital facilities.

“According to UN reports, the first half of 2025 has witnessed a significant rise in the number of civilian deaths, especially in Darfur, in addition to civilian casualties as a result of the shelling of the city of Kadugli in South Kordofan, amid mutual accusations between the two sides of war crimes and genocide in the areas under their control,” he adds.

The erosion of state authority and the collapse of its security and administrative institutions

Abbas says that the military developments on the battlefields are inseparable from the humanitarian dimension, as this war has been classified as “ the worst humanitarian catastrophe the world has witnessed in recent periods, with the dangers and threats it carries not only within Sudan, but also on the region and the international community.”

According to Abbas, the first danger of this war is the erosion of the state’s authority and the collapse of its security and administrative institutions. The reality is that the country is effectively divided between spheres of influence (one army rules one area, and the RSF rules another.)

He explains that the security and police services have collapsed in most cities, as the manifestations of the police have been confined to specific centres and cities, while large areas are witnessing a complete absence of police and a parallel presence of local groups and tribal militias that control entire areas.

Hate and identity killings

One of the dangers facing the country, according to Abbas, is the explosion of violence based on my identity. He says that the conflict has taken on a regional, tribal, and ethnic character, with it being exploited to fuel old conflicts, especially in Darfur, Kordofan, and the areas around Blue Nile, which has led to a significant rise in hate speech and massacres of an ethnic and religious nature. According to Abbas, this escalation in violence and discrimination (sows the seeds of a long-term civil war and is leading the country towards a violent abyss based on identities.)

Terrorism and extremism

Abbas warns that the security vacuum resulting from all of the above, opens the door for extremist groups such as (Al-Qaeda and ISIS) to spread or return, and says: “In light of a long land border that exceeds 6,500 kilometres with neighbouring countries suffering from turmoil, Sudan becomes a fertile ground to form camps and extremist activities, if the security collapse that the country is experiencing continues.”

Abbas warns of the consequences of the current war (including the collapse of the national economy and the worsening humanitarian catastrophe represented by high rates of hunger, destruction of infrastructure, disruption of factories, displacement of workers, suspension of agricultural projects, deterioration of pastures and the environment conducive to livestock).

These factors “in turn fuel the loss of social and economic order, which maximises political and security risks,” he says. The security expert warns of these threats represented in the proliferation of weapons, impunity for accountability, tribal and regional polarisation, and the escalation of hate speech, that they will lead – in the absence of serious intervention – to an unfortunate societal clash in the history of Sudan.

Militarisation and the proliferation of weapons

According to Abbas, the threat facing the country in the near future lies in the militarisation of society and the unprecedented spread of weapons among civilians. He points out that it is easy to obtain weapons and that directives issued by the highest levels in both camps encouraged individuals to arm. He says that the ease of access to weapons has led to the transformation of groups of young people and even children into gun bearers, at a time when education has stopped in large areas. He warns that the militarisation of society is one of the most serious threats to the future of Sudan.

Abbas says that access to weapons is now available and unchecked, and with the flow of weapons across open borders, Sudan has become an emerging market for quality weapons. In this regard, he asks: “Is it reasonable for an ordinary citizen to own a machine gun, a Kalashnikov, or a .42 calibre cannon? He adds: “Is it also possible, which has happened now, that I have a citizen who throws bombs or advanced weapons?). The proliferation of such weapons among civilians is of great concern, he says, because they are not weapons of personal protection but rather tools with a destructive effect, and their social impact is very negative even after any possible peace.

No country

Abbas stresses that “the solution to the crisis of arms and militarisation cannot be superficial or theoretical only but requires a very clear and specific strategy that enables the future civil state to regain control of uncontrolled weapons, through integrated legal, social, political and security measures.” “This strategy should work to reduce stress levels, reduce hate speech, address social injustice, and reconnect the fractured fabric of society.”

He stresses that confronting this danger is not simple, but requires integrated institutional work that includes state agencies, the rules of society and all societal components. According to Abbas, Sudan today does not have an actual state, as much as it has two conflicting powers, and the absence of modern state institutions (services, education, health, security, economy, and development) is one of the fundamental causes of the crisis. (At the same time, pervasive ethnic and regional polarisations further complicate the scene.) Despite this, Abbas expresses cautious optimism, in light of the presence of an “international, regional and local movement” that seeks to restore peace and build a Sudanese state. He cited the existence of countries in the world that went through devastating wars that were then able to build strong modern states by benefiting from experience. He stresses that the road is not easy in light of the current situation, but it does not mean giving up.

Terrorism and violent extremism

Abbas warns that Sudan is moving at an accelerated pace towards becoming a “hotbed of violent terrorism” if the war does not stop immediately and urgent measures are taken to rebuild the state.

He adds that Sudan occupies an ideal geographical location in the African continent and Arab countries, and like most countries, it shares open borders with seven countries, all of which suffer from

He explains that the political turmoil and the control of the (Islamic extremists) in the reins of power for three decades from 1989 until the fall of their regime, and the entry into the current war, with all their weight and at the forefront, in addition to their very extensive relations, with extremist Islamic groups, clearly indicate that Sudan is on its way – if we do not remedy it now – to become the largest focus of terrorism and violent extremism.

He considers that these groups associated with political Islam (do not recognise national borders or the legal jurisdiction of states) and adds:( “They have no so-called “this is the state of Sudan, and this is Chad, Egypt or Libya, all of these are for them, their land is where they move as they wish.”

He stresses that the security conditions in Sudan, and the spread of violence accompanied by extremism, ethnic and regional discrimination, and other social distortions, have enhanced the chances and possibilities of Sudan becoming an incubator state for terrorism and violent extremism. He points out that the failure of the state, in resolving the deteriorating political and economic situation, and then the outbreak of war, contributed to providing a fertile environment for the activity of extremist groups.

History and activity of terrorism in Sudan

Regarding the history of terrorism and its activity in Sudan, Abbas stresses that the warnings of terrorist activity in Sudan (deepened after the Sudanese Islamic Movement seized the reins of power in a military coup in 1989 led by the ousted President Omar Al Bashir, and their adoption of the Islamic state). He stresses that “ the war and the geopolitical reality of Sudan, and the control of Islamic extremists in the reins of power for three decades, and their creation of an incubator that is identical with their thoughts, visions, and their opening of the doors of Sudan, to most of the world’s terrorists, from ISIS, Boko Harem, takfiris and others, have made Sudan a candidate, to be an incubator for violent and extremist terrorism.”

In this regard, he cites the world’s description of the Islamist government, which came to power in 1989, as a “terrorist government that is a safe haven for terrorists and a supporter of them.” He adds: “This classification did not come out of thin air, but came as a result of the behaviours and actions that were associated with the behaviour of that government, as it was later documented that it had official associations with facilitation, or support, extremist activities, as it was already proven that the Sudanese government was behind it.”

Historical evidence of terrorism

Regarding the identity of the groups practicing terrorism, which took many forms after the April 15, 2023, war, Abbas refers to the extremist political Islam groups, which he says are very active in Sudan, as these groups have attracted young people under different names, to engage in this holocaust.

He stresses that the goal of the political Islam groups behind all this is not to establish a state of Islam and Islam innocent of them, or the civil state of Sudan, but their main goal is to return to power again after the Sudanese people overthrew them in the glorious December Revolution.

He stresses that misguided or deviant ideology always leads to terrorist acts (as a result of the clash of ideologies among Islamists, violent events took place in Sudan in which my victims were killed and wounded). In this regard, he refers to historical models and practices that show the relationship between the state and the activities of extremist groups in Sudan.

Multiple domestic terrorist incidents

Abbas mentions a number of incidents and examples, starting with the incident of targeting the Ansar El Sunnah Muhammadiyah mosque in Omdurman in (1994) which killed about 20 people, followed by the involvement of the Islamic regime of Bashir in the failed assassination attempt of Egyptian President Mohamed Hosni Mubarak in 1995, followed by the events of the El Jarrafa Mosque in 2000 that left 25 Killed and more than 20 wounded, then the Salameh cell in 2007, and then the assassination of American diplomat John Granfield in Khartoum (2008). This is in addition to the two bombings of the El Dunder Cell, the Jabra neighbourhood south of Khartoum on September 28 , 2021, and the Hajj Youssef Cell, in addition to activities among university students, the presence of elements linked to Boko Haram in Darfur, the Al-Qaeda cell, and the activities of Sudanese youth who joined organisations abroad. All these models show that these organisations did not resort to ideology or dialogue, but rather violence as a method to achieve their goals, he says.

The current war as a fuel for extremism and terrorism

Abbas expresses his belief that this current war has fuel, represented in the societal motivation to align with the war, adding : “ There is a line-up today, one on the side of the army to resolve the Rapid Support, and the other with the Rapid Support for victory and seizure of power in Khartoum.”

He stresses that the two sides of the war have taken a set of (immoral) motivational means to attract young people to continue the war.

He explains that these means rely on a religious discourse that is mobilised on the one hand, and a racial, regional, and ethnic discourse on the other.

Islamists and foreign fighters

Abbas confirms the recruitment of foreign elements within the line-up and mobilisation operations in the ongoing war today, as the Rapid Support and the Sudanese Army used foreign fighters in the war.

He explains that the alignment of Islamist groups with the Sudanese army in this war (not out of love for the army, but only to restore their regimes, return them to power, and rule Sudan again). He adds, “If we go back to history, we find that these Islamist groups did not trust the Sudanese army,” he continues, explaining that “we saw when the Islamists and the Islamic Movement took power, they established parallel armies out of fear of the Sudanese army, and the first step was to establish the People’s Defence Forces as a parallel force, and it failed, then they established the Border Guard Forces, then they failed, and then they established the Rapid Support Forces” – the second party in the ongoing war today.

Accordingly, Abbas confirms that the Islamic Group (GSM) “historically does not trust the Sudanese army and expects it to turn against it at any moment, so their alignment with it is interim and expedient.”

Local factors for the growth of terrorism

Abbas says that Sudan is facing several local, regional, and international factors that motivate the growth of the phenomenon of terrorism.

He explains that the first factor, (local), is the weakness of the security institutions, which he says that “even before the outbreak of the war, they did not have sufficient capabilities to impose control and prevent the spread of terrorism, pointing out that this security gap has contributed to making Sudan vulnerable to the same threats that have exhausted the world in Syria, Iraq and Europe.”

The second factor is the proliferation of weapons and their illicit trafficking (which has made the environment more fertile for the growth of extremist movements), he says, while the third factor is the extremist mobilising rhetoric in support of terrorism. This rhetoric has legitimised violence through ongoing religious sermons that incite young people to engage in terrorist acts, he says.

The fourth factor is the economic, service, and social imbalances that Sudan is experiencing, he says, including the wide disparities between citizens, which has led to the entry of some Sudanese into the ranks of extremist organisations.

In this regard, Abbas points out that Sudan itself (at one time was a source of terrorists, as the country witnessed the return of ISIS fighters in the Levant, in addition to smuggling Sudanese to join the Somali Al-Shabaab movement.)

Identity, documents, and open borders are a dangerous vulnerability

Abbas stresses that the fifth factor is the imbalance and weakness in the identity systems and documents, which helped in the expansion of terrorism, pointing out that Sudan, as a country with overlapping borders and the existence of common ethnicities with neighbouring countries,

He stresses that the former regime over-granted Sudanese citizenship to foreigners from religiously and politically troubled areas, whether in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen.

He says that the “ousted president” Omar Al Bashir granted citizenship to thousands of foreigners, including those who are wanted internationally. He continues: “I commend the government of the transitional revolution headed by Abdallah Hamdok and the Minister of Interior at the time, Ezzeddine Al-Sheikh, took steps to address this chaos by counting and reviewing those national figures, which exceeded 16,000 naturalisation cases,” he says, explaining that this measure reflects the extent of the overreach and sovereign negligence in the Sudanese identity file.

Cross-border factors and weak regional security and intelligence coordination

Abbas points out that there are several factors that have contributed to the growth and spread of the phenomenon of terrorism and violent extremism, including the ease of movement across Sudan’s borders, which extend for more than 6,500 kilometres, and with countries affected by instability.

He stresses that the weakness of regional security and intelligence coordination, and the weakness of control and control, due to the lack of technical and legal control systems in all countries of the region, make the movement of terrorists and the exchange of weapons an easy and easy process. He points out that there are specific border areas that are used as routes and routes for the movement of extremist elements to and from Sudan, which have helped in the growth and spread of terrorism in a very disturbing way in the sub-Saharan Africa region, as well as in the Sudan region and the surrounding countries.

However, Abbas says that Sudan has not yet become a hotbed of terrorism and violent extremism, but if this war does not stop, Sudan will become the largest hotbed of terrorism and violent extremism.

Geographical areas of crossings for fighters

Abbas identified a number of geographical areas that contributed to the infiltration of these terrorist groups and says: “As for the eastern border of Sudan, we find it disturbed, not only, because of the April 2023 war, but it is old dating back to the conflict between Sudan and Ethiopia over the El Fashqa area.” He explains that this area – El Fashqa – has a security fragility that has made it the only route for exporting terrorists to al-Shabaab in the Horn of Africa.

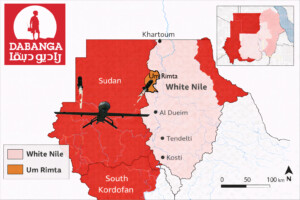

The western region of Sudan – Darfur and Kordofan – is home to terrorist organisations such as al-Qaeda in the Maghreb (AQIM) and Boko Haram, he says, as these groups move across the open border on the border strip linking Chad, Sudan, and Central Africa.

He says that the border with South Sudan, although it has not seen the ideological activity of extremist groups, suffers from security fragility (it may become a crossing point for the arms trade).

Regarding Central Sudan, he explains that the regions of Central and North Sudan and Khartoum are active in terrorism and extremism, pointing out that many incidents have occurred in those areas. He adds, “All of this paints a picture about the situation of terrorism and its future in the Sudan region, whether on its eastern, western and southern borders or at the level of central Sudan.”

War crimes and ideological activism

Abbas points to the importance of distinguishing between the war crimes currently being committed by both sides of the war, such as (killing on the basis of identity, torture, mutilation of corpses, amputation, burning of prisoners, targeting civilians, places of worship and civilian objects).

He stresses that all these crimes are classified as war crimes and crimes against humanity, which are covered by international law and the International Criminal Court.

He stresses that what he is concerned with terrorist groups and violent extremism that the world talks about and warns against, is that terrorism based on ideological principles and linked to extremist religious and Islamist ideas such as the terrorism of ISIS and Al-Qaeda. This terrorism does not believe in the borders of the Sudanese state, but rather poses a threat to Sudan, its surroundings, and the region in General.)

Abbas warns against such terrorism, which he says could be a threat to the world (such as what happened in Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq, where these countries were not only affected by it, but its influence extended to the whole world, and its cells have become spread in all countries in Europe, America, Africa and elsewhere). He warns that Sudan “if this war does not end, it could become one of the biggest spawning sources of this kind of terrorism that is very disturbing internationally.”

Steps to stop the war

Regarding what can be done now to stop this war, Abbas warns that it is necessary to first acknowledge that this war has roots, and not a war made by chance. He adds: “It must be acknowledged that this war has ancient roots and is related to development and identity, and to answer the question of how to govern Sudan, not who rules Sudan.” In this regard, he calls for the recognition that this war is not affected by Sudan alone, but by the region, and therefore, as Abbas says, “The way to deal with it requires finding a solution to this tragedy, with a Sudanese skill, with consistency, coordination and cooperation, with the regional community.” He calls for “maximising the narrative of peace and aligning itself with it by building a major civil front to stop the war, in the face of the army’s narrative that promotes the war of dignity and the narrative of the Rapid Support Party, which promotes justice and support for the margins.” He adds: “As long as there is a bloc that lines up on the side of both sides of the war, we must strive to develop the bloc that rejects both sides of the war… I refer here to the Sudan Peace Initiative advocated by Francis Deng and is an honest initiative to develop and increase a genuine and peace-loving bloc, not war.)

Quartet statement and conflict resolution

Abbas calls on the regional and international community to pay attention to what is happening in Sudan and pay attention and coordinate with the Sudanese solution under the leadership of Sudan, because the impact of the war, as he says, is not limited to Sudan alone, but extends to the region.

In this regard, Abbas praises the statement of the “Quartet Mechanism” , which called for stopping the war, ending its roots, and restoring Sudan to its civil democratic path through a transitional process that turns into a sustainable political process that ends the tragedy of the Sudanese, considering that the statement is one of the most important recent regional and international activities aimed at ending the crisis.

Stopping the war and the future of Sudan

Abbas calls for directing all efforts at this stage to stop the war. Stopping the war does not necessarily mean ending the conflict immediately but is the first step in a long path that requires many actions. He considers that these measures must start with urgent humanitarian operations to address the deteriorating health, medical and food conditions, and then move on to building a coherent and strong transitional authority with clear goals, while at the same time seeking to rebuild Sudanese society.

However, he notes that the process of restoring society is not easy, but rather a complex process that includes transitional justice, balanced development, the establishment of asymmetric federalism, the removal of grievances, and addressing the roots of conflict, whether it is related to power, identity, or social development.

He stresses that any ceasefire (without addressing the roots of the crisis that caused the war) would only postpone the conflict for a period of time, before it was renewed again. He stresses that Sudan needs today before tomorrow an integrated project to end the conflict once and for all, starting with stopping the war and ending with a lasting and comprehensive peace.

and then

and then