Report: Denial of freedom of LGBTQ+ artistic expression in Sudan

At least three LGBTQ+ organisations in Sudan are forced to operate underground, forcing artists to work with virtually no financial support, according to a report published on December 10 by Freemuse. In an interview with Radio Dabanga, Ola Diab, a Sudanese journalist based in Qatar, said that there is “still significant resistance in Sudan – politically, socially and religiously.”

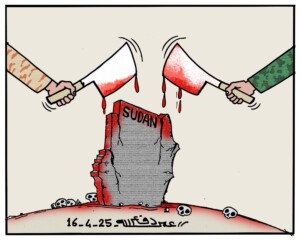

Graphic by Sudanese queer activist and visual artist Malab Alneel (Social media)

Graphic by Sudanese queer activist and visual artist Malab Alneel (Social media)

At least three LGBTQ+ organisations in Sudan are forced to operate underground, forcing artists to work with virtually no financial support, according to a report published on December 10 by Freemuse. In an interview with Radio Dabanga, Ola Diab, a Sudanese journalist based in Qatar, said that there is “still significant resistance in Sudan – politically, socially and religiously.”

In July 2019, Freemuse spoke to two anonymous activists from Sudan who operate an underground gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, transsexual, queer, and other (LGBTQ+) artists’ organisation. According to the activists, “at least three organisations in Sudan are forced to operate in this way – illegally and with no bank accounts.”

The Freemuse report, Painting the Rainbow: How LGBTI Freedom of Artistic Expression is Denied, highlights 149 acts of artistic violations against LGBTQ+ persons and art documented between January 2018 and June 2020.

It is virtually impossible to register LGBTQ+ organisations in the country, “despite human rights organisations’ attempts to legally challenge discriminatory national legislation.” Homosexuality was punishable by death penalty nationwide, a policy brought in under British colonial systems of justice, until very recently. In July, the government announced that the punishments will be reduced to prison terms, ranging from five years to life sentences, although this is not confirmed.

Fabo Elbaradei, an LGBTQ+ activist based in the capital Khartoum, welcomed the surprise move to lift the death penalty but said it would not change life much for gay people in Sudan. “We are subjected to social discrimination and we face a prison sentence … for simply being who we are,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation in emailed comments. “We are still deprived of our right to live like any other members of society.”

According to the report, legal hurdles “prevent organisations from establishing and institutionalising long term stability in their project work. Such situations also affect their ability to engage with artists and support or promote their work within their organisational activities. For this reason, many artists are compelled to work with virtually no financial support.”

Radio silence

Interviewees from Sudan who took part in the research also claimed that “local media do not report about LGBTQ+ issues.” During the regime of deposed Omar Al Bashir, several international media outlets were not allowed to operate in Sudan and the Sudanese media were systematically suppressed. This grew even worse after the start of the uprising in December 2019.

In the Reporters Without Borders 2019 World Press Freedom Index, Sudan ranked 175 out of 180 countries. In 2020, Sudan rose to 159, due to “the provisional constitution adopted for the transition [which] guarantees press freedom and internet access.”

Although progress has been made, the media freedom situation in Sudan is “still below the standards set by the transitional government, that was founded on freedom, peace and justice,” said Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok on May 3 last year. Today, draconian laws that the old regime used against the media are still in effect.

“Local media do not report about LGBTQ+ issues”

– Anonymous

“In countries which criminalise homosexuality, artists face many problems in the process of producing queer art,” the report noted. “These obstacles can vary depending on the artform in question. While writers, painters and composers may solely create their work in the safety of personal or private spaces, film and theatre producers are unable to operate in this way, often requiring huge teams to work in different locations. These necessary requirements mean that artistic projects can hardly be produced clandestinely and essentially entail risks for anyone associated with the project.”

Social media

Ola Diab told Radio Dabanga that the LGBTQ+ movement in Sudan is only just beginning, along with coverage of it. “Due to social media, more people are talking about the existence of the LGBTQ+ community in Sudan and their rights in the country,” including Sudanese people who are advocating for LGBTQ+ rights in Sudan, such as Norway-based artist and gay rights advocate Ahmed Umar and queer activist and visual artist Malab Alneel.

Ahmed Umar was featured in The Art of Sin, a documentary about his life and his journey back to Sudan after ten years living as a political refugee in Norway. In Sudan, he says, he is “a minority within a minority within a minority that is oppressed”.

According to Diab, “we're slowly seeing the birth of a Sudanese LGBTQ+ movement, especially after the revolution where many highlighted a new Sudan with rights for all, including those of the LGBTQ+ community. It's happening gradually as the rights of the LGBTQ+ is under the spotlight on the world stage. However, there's still significant resistance in Sudan – politically, socially and religiously.”

When asked about change could come about after the revolution in Sudan, Diab said that even if media organisations begin to report more on LGBTQ+ issues, public backlash would form a strong resistance to change. “With time, media organizations in Sudan and abroad will gradually discuss the challenges the LGBTQ+ community in Sudan face. Even if the laws become more accepting of the LGBTQ+ community, there will be a social or community resistance that will come into light in the media – whatever the form,” she said.

Subversive methods

Despite challenges, organisations continue to overcome unnecessary hurdles and conduct activities. At least 77 countries use criminalisation of homosexuality laws and criminal codes to silence LGBTQ+ artists. Nonetheless, Painting the Rainbow shows that despite different types of discrimination in various contexts, “no laws, traditions, or religions can entirely stop artistic expression around these issues.”

On December 30, a working essay published in Kohl Journal which explores queer use of space against the backdrop of the Sudanese revolution, including the mass sit-in which took place at Military Headquarters in Khartoum and was violently broken up on June 3, 2019, gained traction on Twitter.

In May 2018, members of the local LGBTQ+ community in Khartoum screened the documentary film You Are Not Alone and held a photo exhibition called Ownership Certificate in the Dutch Embassy.

The documentary film Queer Voices from Sudan was published in January 2017, before the fall of Al Bashir and his regime.

Sudanese law requires the obtainment of formal authorisation for filming in public unless working for an official media outlet. Aware of the unlikelihood of securing the prerequisite permissions, the production crew of the documentary made alternative arrangements.

“During digital security trainings organised before they started working on the film, the crew developed detailed plans on how to film on location without being caught and enacted various negative scenarios so that they could identify what they needed to do to if caught filming without official approval.”

A cameraman was arrested by authorities during the making of the film, according to Freemuse. Fortunately, due to his training he was prepared to hand over fake memory cards to the police.

Radio Dabanga’s editorial independence means that we can continue to provide factual updates about political developments to Sudanese and international actors, educate people about how to avoid outbreaks of infectious diseases, and provide a window to the world for those in all corners of Sudan. Support Radio Dabanga for as little as €2.50, the equivalent of a cup of coffee.

and then

and then