Clingendael: ‘Risk of famine very high’ in Sudan

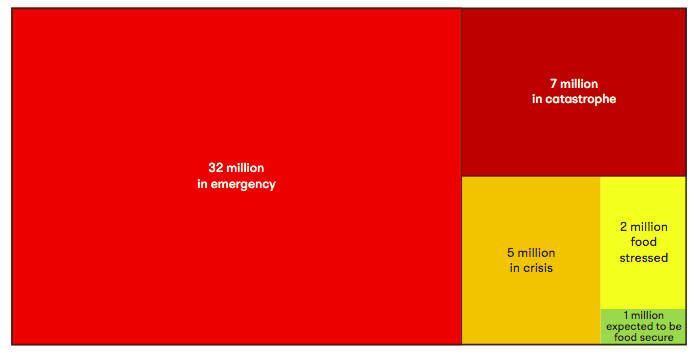

An estimated 7 million people in Sudan are likely to experience catastrophic levels of hunger by June (Graph: Clingandael Strategic Monitor)

According to Clingendael Strategic Monitor, “the conflict in Sudan has a substantial impact on the country’s food system and hinders people’s ability to cope with food shortages.” The country reportedly shows the worst hunger level ever recorded during the harvest season, with the risk of famine very high.

October to February is harvest season in Sudan, and is usually a period when food is more available. “The severity and scale of hunger in the coming lean season (mid-2024) will be catastrophic,” said the Clingendael policy brief published on Thursday.

The brief, written by Senior Research Fellow Annette Hoffman, aims to provide strategic advice and tailor-made solutions to government ministries, companies, business associations, and nonprofit organisations.

The war doubled the percentage of people (35 per cent) enduring crisis levels or worse levels of food insecurity by June, with reduced access to usual coping mechanisms. “Typical coping mechanisms in Sudan include labour migration, sales of firewood or charcoal, the consumption of ‘wild foods’, and the sale of livestock.”

In addition, the demand for agricultural labour will be very limited until June, when planting season begins in Sudan.

As of January, almost eight million Sudanese people were reported displaced. According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Sudan has the largest number of displaced people and the largest child displacement crisis in the world.

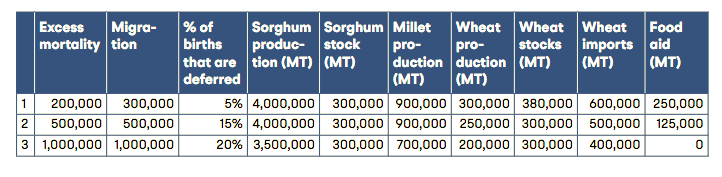

Scenario one, depicted in the table above, is the best-case scenario based on UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) statistics, which are slightly conservative and generous according to Clingendael. It notes an expected excess mortality of 200,000 people and migration of 300,000 caused by “the majority of the population facing extreme hunger by July.”

This means that most of the population will face large food consumption gaps, very high acute malnutrition and excess mortality, or extreme coping strategies to meet food needs, with access to between 800 and 1,200 calories per day.

In scenario two, reportedly the most likely scenario, famine conditions are likely to occur in large parts of Sudan. “About 40 per cent of the population will have access to less than half of the normal energy requirements from June onwards, and about 15 per cent of the population (7 million people) will have access to less than a third of the normal energy requirements” from May to September, notes Hoffman.

Country-wide famine could occur in scenario three, which is the worst-case scenario, but not unlikely.

“About 25 million people including 14 million children are in dire need of humanitarian assistance in Sudan,” a group of UN experts reported on February 1. “We call for increased funding for civil society to assist victims and for humanitarian response to provide life-saving assistance,” they said, warning that the appeal was only 3.1 per cent funded.

From December to January, the harvest season in Sudan, food insecurity outcomes were expected to be “atypically elevated and rising” according to the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), as the “lean season is expected to start atypically early in most areas.” Sudan topped this year’s International Rescue Committee (IRC) watchlist of countries most likely to experience a deteriorating humanitarian crisis.

“Rather than the inevitable consequence of war, this food crisis is the result of the generals’ deliberate destruction of Sudan’s food system and the obstruction of people’s coping mechanisms,” reported Hoffman. “Sudan’s generals have not only produced the worst displacement crisis in the world today. They have also caused the worst hunger level ever recorded during the harvest season in Sudan.”

On Wednesday, United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator Martin Griffiths said that the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), agreed to meet in Switzerland to discuss humanitarian access in Sudan, but added he is “still waiting for the actual meeting to happen.”

The policy brief urged countries and international actors to take action. “Besides increasing diplomatic and economic pressure to stop the war, the EU, its member states, the US, the UK, and Norway, as well as the UN and international non-governmental organisations must urgently and massively scale up meaningful assistance by declaring the risk of famine for Sudan, injecting mobile cash directly to local producers, as well as to consumers and local aid providers, and immediately scaling up food aid and water, sanitation and hygiene support.”

and then

and then