Blocking the passage of goods and merchandise to western Sudan: Another war waged by Khartoum against the people and a threat to the country’s unity

Aftermath of an airstrike that destroyed Tora Market in North Darfur, March 24, 2025 (File photo: RD)

Report by Abdelmoneim Madibu for Radio Dabanga

Amid the ongoing war and the complex humanitarian, economic, and social situation in Sudan, decisions issued by the governors of Northern, Khartoum, and North Kordofan states to prohibit or restrict the transport of goods and merchandise to western Sudanese states have sparked widespread controversy. Some downplay the impact of these decisions on the ground, while others warn of their legal, humanitarian, and political repercussions, as well as their impact on the unity of a country already weakened by the war.

This report examines the impact of these decisions on markets in Darfur and Kordofan, through testimonies from community leaders and traders from Nyala, El Daein, El Fula and Bahr El Arab, along with legal, human rights and political readings that warn of deeper risks that extend beyond the economy to the structure of the state itself.

Decisions

On November 25, 2025, the Governor of the Northern State, Major General Abdul Rahman Abdul Hamid, issued a decision prohibiting the transfer of goods, merchandise, and items to areas controlled by the Rapid Support Forces in Kordofan, Darfur, and western Northern State. The decision stipulated penalties of up to five years imprisonment, a fine of 10 million pounds, and confiscation of goods, merchandise, and means of transport.

Less than a month later, on December 20, the governor of Khartoum issued a decision with the same directives for the ban and penalties that were included in the decision of the governor of the Northern State. A few days later, the governor of North Kordofan issued a decision prohibiting the exit of goods and merchandise from the city of El Obeid to the areas controlled by the Rapid Support Forces in parts of Kordofan and Darfur.

The decisions were met with condemnation from some segments of Sudanese society, who saw them as exacerbating the societal divisions created by the war and threatening the country’s unity. The National Umma Party called on the de facto authorities in North Kordofan, Khartoum, and the Northern State to immediately rescind these decisions, stating that they inflict grave harm on innocent civilians and contradict the most basic duties of the state to protect people’s lives and preserve their dignity.

The party considered these decisions to be the use of food as a weapon to punish civilians, which constitutes a war crime and a flagrant violation of international humanitarian law, exposing the claims of equal treatment for Sudanese citizens without discrimination.

In a previous question posed by Radio Dabanga to its followers on Facebook, 85% of those who interacted with the question rejected those decisions, indicating that they punish civilians in Kordofan and Darfur through their livelihoods.

Impact on Darfur markets

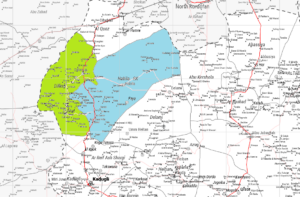

Radio Dabanga spoke to a number of citizens and traders in Darfur states about the impact of these decisions on the markets and their living conditions. Their opinions varied between those who believe that they have an impact on the prices of goods coming to the region from the states whose governors issued these decisions, and those who believe that they are worthless decisions based on Darfur’s openness to a number of countries that supply the region’s markets (Chad, Central Africa, South Sudan and Libya).

Traders in the cities of Nyala in South Darfur and El Daein in East Darfur stated that the decisions issued by some states in eastern Sudan, which prohibit the export of goods to areas in western Sudan, have had little impact on market activity or the availability of basic commodities.

A merchant in Nyala’s main market explained that goods are available in sufficient quantities, noting that the markets have not experienced any shortages of food or building materials, despite the announced measures. He added that goods are now arriving from alternative sources, including South Sudan, Chad, Libya, and the Central African Republic, which has contributed to market stability and diversified import options.

The merchant confirmed that goods such as sugar, flour, pasta, oils, sweets, and building materials are currently available, some at lower prices compared to the goods that used to arrive from eastern Sudan, stressing that the market has not been affected by the recent decisions, which he described as decisions on paper.

Trader Karam El Din El Tahir El Bashari from the city of El Daein in East Darfur said that markets in Darfur in general have witnessed remarkable stability in the availability of goods since the outbreak of the war, explaining that basic food supplies such as flour, sugar and tea are available in sufficient quantities, without recording significant price increases.

He added that supplies coming from neighbouring countries, especially South Sudan, Chad, and Central Africa, have contributed to ensuring the flow of goods to the markets, stressing that the commercial situation in El Daein is stable, and buying and selling is proceeding normally.

The two traders confirmed that Darfur markets have become less dependent on supplies coming from Khartoum or the North, noting that the current alternatives have provided relative stability in the markets, and reassured citizens that basic commodities are available and there is nothing to worry about at the moment.

In this context, Mayor Musa Issa Hamid, the official in charge of the local government’s livelihoods in Bahr El Arab locality, downplayed the importance of the decision to prevent goods and merchandise from reaching Darfur, saying that these decisions do not have any negative impact on the local community.

The mayor added to Radio Dabanga, “The community in Darfur relies on alternative local and regional sources, and materials coming from neighbouring areas are more efficient and beneficial compared to what comes from the North or Khartoum.”

He added that the local community does not depend on these goods coming from the states of Khartoum and the Northern State, so I say, “The ban decision is hollow and does not affect us in any way.” Mutasim Adam El Dhay from El Fula city in West Kordofan went in the same direction, telling Radio Dabanga that the decisions have no effect on the markets in the state, given that the state has been completely deprived of goods and merchandise coming from eastern Sudan since the outbreak of the war, and has therefore opened up to South Sudan and Chad to import its basic needs. However, he added that after the outbreak of the war, only one gateway remained to deliver a few goods from Ad-Dabba to El Fula via the Ghabish area, but it stopped because of these decisions, without there being any effect of its stopping on the markets.

Slight increase in prices

Despite assurances from several traders that the decisions had no impact on the markets in Darfur, Ismail Ibrahim Hassan, a trader in the large market in Nyala, believes that there is a slight impact of the decisions on the region’s markets, pointing to a tangible increase in the prices of goods that traders import from the eastern states of Sudan, such as (lentils, salt and rice), where the price of 20 kilograms of lentils increased from 100,000 to 130,000 pounds, and 50 kilograms of salt from 100,000 to 150,000 pounds, an increase ranging between 30 and 40%.

He explained that this price increase directly impacted citizens and consumers in the city. Hassan noted that some goods are imported via supply lines from the east, while others come from Libya or Chad, and that the state’s civil administration is working to find alternatives to facilitate the delivery of essential goods. He added, “Efforts are underway to ensure the continued availability of basic commodities, while addressing some issues related to the import process to guarantee price stability in the state.”

The market in El Daein experienced some initial disruption in the days following the decisions, with prices of some goods rising significantly. Journalist Mohamed Saleh Triko, reporting from the city, told Radio Dabanga that goods coming from eastern regions, such as sugar, flour, biscuits, and milk, saw price increases in the first few days after the decision was implemented. Meanwhile, the prices of iron and various types of pipes rose so sharply that some traders temporarily halted sales. They later resumed selling after prices stabilized, either due to sufficient supply or through the smuggling of some goods.

The journalist noted that Darfur relies on alternative supply sources, with goods such as sugar, tea, and milk reaching East Darfur from South Sudan, while other goods reach West Darfur from Chad and El Fasher from Libya at relatively stable prices. The region’s inhabitants also depend on fuel coming from South Sudan and Chad.

The journalist cited the impact of the decisions on the region’s market, pointing to the price hikes that occurred in the fall. He said, “During the fall, prices were high due to the disruption of the road between Darfur and the eastern states. However, in September, when the first shipments arrived from the city of Ad-Dabba, they contributed to lowering prices. In addition, in the first days following the decision of the governor of the Northern State, there was a rise in the prices of sugar, flour, and biscuits, along with a rise in the prices of iron and zinc, which forced traders to stop selling because these goods came from the eastern states. But after a few days, they resumed selling, and prices stabilized without rising.”

Violation of international law

Commenting on the three decisions, writer, and political analyst El Tijani El Hajj said they lacked legal basis, arguing that state authorities (governors) do not have the power to prevent the flow of goods within the country, even during internal conflicts. He explained that the decisions contradict international humanitarian law, which prohibits the use of food and basic necessities as a means of coercion or a weapon in armed conflicts.

El Tijani El Hajj told Radio Dabanga that preventing goods from reaching areas controlled by other parties to the conflict directly affects civilians, which may put those who issued and implemented these decisions under accountability according to the rules of international humanitarian law, adding that this step can be interpreted as a form of collective punishment.

For her part, human rights activist, and political advocate Hanan Hassan stated that the decisions to ban the transfer of goods contradict the principle of freedom of movement and the exchange of goods and services, a principle guaranteed under the Transitional Constitutional Document. She argued that any such restriction is only legitimate under strict conditions, including a clear legal framework, a specific timeframe, and a legal justification based on an extreme necessity—conditions which, she asserted, are not met in the recent decisions.

Hanan added to Radio Dabanga that preventing or obstructing access to basic goods, such as food, medicine, and fuel, to areas suffering from armed conflict or critical humanitarian conditions, is a violation of the right to life, food, and health, which are constitutionally and internationally protected rights.

She noted that these practices could be legally classified as using starvation or deprivation as a tool of coercion, which, in some contexts, could amount to war crimes. Hanan Hassan warned that the continuation of these decisions could exacerbate humanitarian crises and lead to a sharp rise in prices.

Politician and former minister Nahar Othman Nahar described the decisions as unjust and directly affecting the interests of civilian citizens, warning of serious humanitarian and economic repercussions that could fall under the category of internationally prohibited collective punishment.

Nahar told Radio Dabanga that these decisions target ordinary citizens before any military party, noting that civilians in cities like Nyala and Tawila and large areas of Kordofan will be directly affected, especially the most vulnerable groups, such as children and the sick, who depend on access to milk, diabetes and blood pressure medications, and life-saving treatments.

He added that the decision practically means depriving civilians of basic needs, asking: If a family resides in Nyala or Kordofan and has a child who needs milk or a sick person who needs medicine, how will these materials reach them under this embargo?

Nahar criticized the silence of the political leaders and the people of Darfur and Kordofan states present in Port Sudan regarding these decisions, even though the decisions directly affect the social bases of those political forces.

He stressed that political or military differences do not justify halting trade, citing the continued trade between Sudan and South Sudan despite the secession and political disputes, in addition to Sudan’s trade relations with neighbouring countries and the world, stressing that political disagreement has never been a reason to cut off trade.

The former minister considered that these measures could be classified as war crimes if it is proven that they lead to the starvation of civilians or deprive them of treatment, pointing to what he described as the blatant contradiction in government policies, as he pointed to the continued flow of Heglig oil revenues, part of which he said goes to the Rapid Support Forces, as part of an agreement to pay $10 million a month, while medicines and food are denied to civilians in Darfur and Kordofan.

Nahar called for raising public awareness of the seriousness of these decisions, demanding that the issue be brought to the attention of human rights organizations, given that preventing the movement of food and medical goods within a single country represents a clear violation of human rights.

The National Umma Party said in a statement seen by Radio Dabanga that these decisions reveal the use of food and basic needs as a means of collective punishment against innocent citizens who have no fault in the outbreak of war, and who were not the cause of the presence of any armed forces in their areas, and it is an attempt to pressure to displace citizens from their areas to other areas.

The National Umma Party called on the governors of the three states to reverse these decisions, which it said cause great harm to innocent citizens and contradict the most basic duties of the state to protect people’s lives and preserve their dignity.

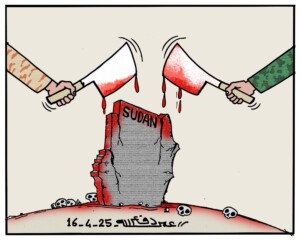

Tearing apart the country’s unity

Several people who spoke to Radio Dabanga about these decisions expressed their fears that they would lead to the dismantling of the country’s unity. Writer and political analyst El Tijani El Hajj described the decision as ill-advised, because it leads to many dangerous indicators, most notably that it seems as if these states are seeking, through preventing food, to separate regions from the rest of Sudan by preventing trade between regions, which is a very dangerous trend that increases the gap between different communities, whether in western Sudan or in the central regions of Sudan, as he put it.

In an interview with Radio Dabanga, El Hajj pointed out that these decisions are considered a form of collective punishment under international humanitarian law, and that even if they are not implemented or adhered to, politically they reinforce the principle of the division of the state and the division of societies, which puts decision-makers in the position of those who want to threaten the unity of the country or seek to fragment it and its societies, which are already affected by the war, and makes matters worse on the existing situation.

Meanwhile, Hanan Hassan warned that the political and social repercussions of these decisions include deepening the feeling of marginalization and regional division and undermining the idea of a single state and a unified market.

Meanwhile, politician and former minister Nahar Osman Nahar pointed out that the Rapid Support Forces control open borders with Chad, South Sudan, and Libya, and have access points even through Ethiopia, which enables them – according to him – to provide supplies to their fighters, while unarmed civilians remain the main victims of the embargo.

The former minister warned that such decisions increase tension and threaten the unity of the country, referring to what he said was a leaked letter from former Foreign Minister Ali Youssef last February, in which he spoke about trends within the Port Sudan government to confine the Rapid Support Forces to Darfur and Kordofan, considering that any attempt to separate or isolate specific regions represents a fragmentation of Sudan, something which he said any Sudanese who is keen on the unity of the country should reject.

The National Umma Party views these decisions as using food as a weapon to punish civilians, which constitutes a war crime and a flagrant violation of international humanitarian law. It also exposes the claims of the de facto authority in Port Sudan regarding the treatment of Sudanese people on an equal footing without discrimination – as they put it. Traders in Kordofan and Darfur report that markets in both regions have so far managed to absorb the impact of the ban on transporting goods by relying on regional alternatives from neighbouring countries. This has contributed to the continued availability of essential commodities and relative stability in trade. However, political, and human rights analyses place these decisions in a more dangerous context, arguing that they lack legal basis and may constitute serious violations of international humanitarian law, including the use of food as a tool of coercion or the imposition of collective punishment on civilians. Furthermore, they threaten the unity of the country, which has become increasingly fragile and is diminishing with the continuation of this war.

and then

and then