Sudan’s looted memory – the identity of a homeland at stake

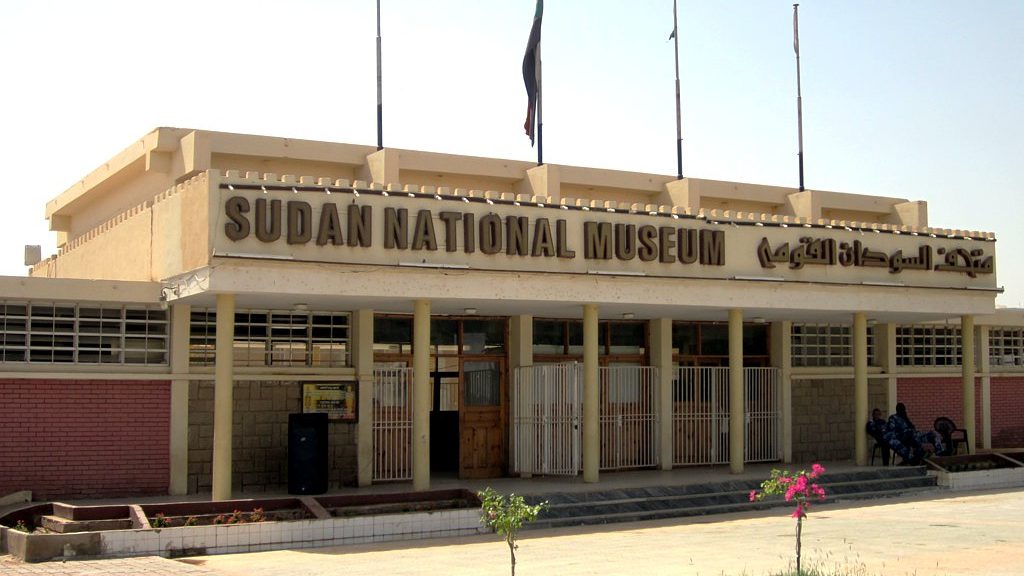

Pre-war view of the Sudan National Museum in Khartoum (File photo: Sudan News Agency)

Report by Mohammad Morshed / Jabraka News for Sudan Media Forum

Since the outbreak of war in Sudan in mid-April 2023 between the army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), museums, archaeological sites and cultural institutions in the capital Khartoum have suffered heavy damage, most of which are located in areas that have witnessed the fiercest battles, making them vulnerable to direct shelling and acts of vandalism that have lasted for about two years, while systematic vandalism and looting with the aim of erasing the nation’s history has not been ruled out.

The National Museum of Sudan, the most important institutions and museums that have been affected by the war in vandalism and looting, the memory of the nation and the treasure of its civilisation, which is located at the junction of the Nile on Nile Street in the center of Khartoum, is the greatest heritage value in Sudan, a building and a meaning, as it contains collections representing all periods of Sudanese civilisation, from prehistory, starting from the Stone Ages through Nubian and Christian antiquities to the Islamic period. It houses thousands of artefacts and statues of great historical and material value, including pottery, stone, and gold pieces dating back thousands of years.

Systematic looting and a campaign to recover artefacts

The acting director of the Sudan National Museum, Ghalia Jar Al-Nabi, told “Jabraka News” that the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have systematically targeted Sudanese museums to erase the history of Sudan, as the Sudan National Museum includes more than 100,000 artefacts representing the history of Sudan from the Stone Ages to Islamic times. More than 60% of the artefacts were looted, including metal, pottery, gold and jewelry belonging to the kings and queens of Nabata, and the rest was vandalised, including records that document the artefacts.

Jar Al-Nabi pointed out that Sudan’s archaeological treasures looted by the Rapid Support Forces have been smuggled beyond Sudan’s borders to regional and international markets, adding: “They will most likely be sold for small amounts compared to their historical and civilisational value, which makes it almost impossible to recover them in light of the lack of accurate documentation of the artefacts.”

She pointed out that these attacks on the cultural heritage in Sudan pose a serious threat to the identity and history of Sudan, and that the looted artefacts are not merely material objects, but represent the history of a people and embody its cultural identity and national memory.

She noted that an international team of a number of Sudanese archaeologists, in cooperation with international experts, in cooperation with UNESCO and Interpol, has launched a search process with the aim of recovering thousands of looted artefacts, stressing the need to coordinate international efforts to recover these antiquities and restore the rest of them.

The Khalifa Abdullah Al-Ta’ishi Museum in Omdurman was also looted and destroyed, as its holdings documenting the Mahdi period and before it in Sudan’s history, including rare manuscripts, metal objects, and personal belongings of the leaders of that era, were looted. Among the loot items are the sword of Prince Osman Daqna and Abd al-Rahman al-Nujoumi, the two well-known leaders of the Mahdi Revolt (1881–1899) against Turkish-Egyptian rule.

The destruction continues to include the Natural History Museum of the Faculty of Science at the University of Khartoum, which contains various species of creatures, including live and mummified birds and reptiles, and documents the rich diversity of Sudan’s wildlife and has been preserving specimens of rare species of endangered animals and birds. The specimens contained in this museum are of great importance to students and researchers.

The losses extend to the Sudan Ethnographic Museum, which documents the traditional culture in Sudan, reflects the multiplicity of ethnic groups, and highlights the diversity of civilisations and environments in Sudan’s vast regions, by displaying agricultural, domestic and ceremonial tools, in addition to costumes and other things that express the different regions of the country.

The Geology Museum, the Military Museum and the Presidential Palace were also destroyed, in addition to ancient scientific institutions, cultural centers and many places of worship in the center of the capital, Khartoum.

A nation without data memory

The writer and historian Dr. Bashir Ahmed Mohieldin told Jabraka News that museums in Khartoum state, along with the National Archives House and the National Library, suffered heavy damage as a result of what he described as a “systematic campaign carried out by the Rapid Support Forces” during their control of the capital.

He pointed out that this campaign targeted the national memory of the Sudanese nation, which extends for seven thousand years, deliberately and due to ignorance of its value, which led to the destruction of almost most of the cultural monuments in Khartoum, describing this as “the greatest pain of the national memory”, and a crime for which the Rapid Support Forces are responsible.

For his part, Sudanese sculptor and sculptor Mustafa Bashar told Jabraka News that the disappearance and destruction of antiquities is a loss for the Sudanese people, who relied on them to build a new homeland, as they represent a database that preserves the memory of the nation, and it would have been better to preserve these collections, because after the end of wars, people return to their collective memory in museums.

Bashar added that the history of nations is read through their material effects, and that their loss makes the country without a compass and in a state of weightlessness, especially if the legacy remains confined to oral tales or written texts without physical evidence that expresses the different periods of history.

He explained that the destroyed monuments can be redesigned by Sudanese sculptors, even with the help of modern laser techniques, but stressed that these works will remain mere simulations with no historical value and do not compensate for the original.

Since the start of the war in Sudan, the RSF has taken control of large parts of Khartoum, including the city centre, which is home to these important archaeological and cultural sites. Since then, a series of international and local accusations of tampering with and vandalising these sites and using them as military barracks have continued against these forces, before the army was able to expel them and regain control of Khartoum in May 2025.

Documents and Manuscripts in the Circle of Damage

On the other hand, Dr. Bashir points out that the documents and manuscripts in the National Archives were damaged after the windows were smashed, and they became vulnerable to rain, wind and moisture. Some documents were taken out of their containers and scattered on the ground, he said, and some of them, especially old newspapers, were affected, noting that the general condition is assessed as “relatively excellent” given that the building is located in an area that has witnessed active military operations near the army’s General Headquarters.

In this context, the president of the Sudanese Association for Libraries and Information and a professor at Omdurman Islamic University, Prof. Yousef Issa, told Jabraka News that many documents, manuscripts and archived materials, including those of state agencies, have been severely damaged not only due to the effects of the war, but also by natural factors, such as rains that the roofs could not prevent leakage, in addition to the spread of rodents and fungi, which exposed them to damage. The professor called for the need to take into account the materials used in the construction of cultural buildings in the future to ensure their protection.

Dr. Bashir Mohieldin noted that documents that are completely or partially destroyed can be tried to retrieve their copies from the assets in the houses of other documents, stressing that rescuing what remains is an urgent national responsibility. He pointed out that it launched the “Dr. Bashir Ahmed Mohieldin to save what can be saved at the National Archives,” he said, adding that the initiative found support from government agencies.

Regarding the possibility of restoration, Mohieldin explained that it is very difficult to compensate for the lost antiquities, because the artefacts are unique and cannot be replaced.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) launched an appeal in a statement in late 2024, calling for an end to “the acquisition, participation in the import, export or transfer of cultural property coming from Sudan,” stressing that any illegal sale or transfer of cultural assets leads to “the disappearance of part of Sudan’s cultural identity and undermines the country’s ability to recover”.

UNESCO’s tightening came after the publication of identical reports and photos, accusing the RSF of displaying valuable archaeological collections from the National Museum for sale on the Internet, at low prices, indicating that their historical and material value is not known.

Regarding the efforts to save archaeological sites, Dr. Mohieddin pointed out that immediately after the announcement of the army’s recapture of Khartoum and its evacuation from the Rapid Support Forces, a number of interested people, historians and initiators moved to monitor the situation in the museums and the Documentation House, and transmitted what they saw through videos and audio recordings to the competent authorities. They carried out clean-up and sanitation operations and removed rubble, explosive remnants and shrapnel, which restored the “bright face” of the Documentation House, he said.

Visual artist Mortada Jadin expressed his displeasure over the loss of many archaeological collections of high aesthetic and artistic value, describing their loss as the loss of future generations, and wished that a civilian government would come to help recover the vandalised and looted works, pointing out that Sudanese artists are able to recover many works because they carry the memory of these treasures and their connection to them artistically and spatially.

Although there are no accurate reports estimating the extent of the losses to cultural and civilisational sites, those interested in the assessment indicate that the loss of most of these institutions, which are based in the capital, Khartoum, requires a redoubling of the concerted efforts of all local and international cultural stakeholders in Sudan to bring it back to life.

Reform efforts

Prof. Issa pointed out that they at the Sudanese Library and Information Association, a professional and voluntary body, have started to count the institutions affected by the war, including all university and public libraries, with the aim of preparing a detailed report supported by images showing the extent of the damage and the time period that will take to repair, and this report will be presented to international and regional organizations to discuss ways to provide assistance in the reconstruction of these facilities.

He stressed that the implementation of these cultural projects is proceeding according to well-thought-out plans, and that they are working to develop cultural institutions better, in addition to working to raise awareness of the importance of these cultural projects and how to preserve and deal with them. This includes information houses, museums, theatres, cultural centres, publishing houses, booksellers, and personal collections, with future plans to deal with these resources.

Regarding efforts to pursue looted antiquities, the Sudanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs said in a statement in early April 2025 that the government will continue its efforts with UNESCO, Interpol, and all organisations concerned with the protection of museums, antiquities and cultural property, to recover the loot and hold those responsible accountable. She pointed out that what has been done is considered a war crime under Article 8 of the Rome Statute, the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in Conflict, and the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Prohibition of Trafficking in Cultural Property.

This article by Mohammad Morshed of Jabraka News is published via the platforms of the Sudan Media Forum and its member institutions to shed light on the extent of the widespread destruction, looting and devastation that museums, the National Archives and libraries in Khartoum were subjected to, during the battles, which led to the loss of an estimated percentage of invaluable archaeological collections and treasures, and damage to manuscripts due to nature and neglect, which threatens the memory of Sudanese civilisation. Efforts are being made to recover the looted artefacts and repair the damage.

Find the Sudan Media Forum on Facebook and on X: #StandWithSudan #SilenceKills #الصمت_يقتل #NoTimeToWasteForSudan #الوضع_في_السودان_لايحتمل_التأجيل #Stand #SudanMediaForum

and then

and then