Land justice, drought, and desertification: How a Sudanese town is standing up for its rights

Catchment areas in Sudan (Fie photo: UNEP)

By Sarah Burroughs

On June 4, hundreds of residents of Wadi Halfa, Northern State, blocked all major entrances to the town, preventing trucks from passing. The protesters told Radio Dabanga that they were upset about scheduled power outages, which led to disruptions in the water supply and forced bakeries to shut down. As the annual World Desertification and Drought Day is observed globally today to raise awareness and promote solutions to desertification, land degradation, and drought, the Wadi Halfa protest and blockade are indicative of the public despair in as much as half of Sudan, where chronic water shortages – exacerbated by fuel and power outages – threaten peoples’ access to this essential need for life.

While accurate recent figures on desertification and drought in Sudan are difficult to ascertain amid the current conflict, a study published in the ARPN Journal of Science and Technology in 2015 identified Sudan as “one of the most seriously affected countries by desertification in Africa.” Over half of the country lived in areas affected by desertification when the study was published.

The UNESCO definition of desertification is “the degradation of land in arid, semi-arid, and dry sub-humid areas; it is caused primarily by human activities and climatic variations and affects the world’s poorest.”

Recurrent droughts and the resulting desertification have considerable effects on agricultural productivity in Sudan, particularly in terms of reducing the water available for agricultural production, according to the Red Crescent Climate Centre (RCCC).

Wadi Halfa climate

As one of the largest of the 18 states in Sudan, Northern State has an estimated population of just under 1 million. It meets Egypt and Libya to the north and is surrounded by North Darfur, North Kordofan, Khartoum state, and River Nile state to the south. The Nile emerges from the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum, the capital city of Sudan, and runs from River Nile state into Northern State, where it arcs north, leaving the state and the country at Wadi Halfa, which is situated near the northern border with Egypt.

Northern state is a combination of inland plains of the Nile and an extensive expanse of stony deserts with dunes drifting over the landscape. A fertile sliver runs through it along the river, where the majority of people live, surrounded by desert. Northern Sudan receives a mean annual rainfall of 100mm per year, and summer temperatures often exceed 43°C.

Therefore, people in Wadi Halfa are heavily reliant on water from the Nile, which runs through nine countries to reach the town. They also rely on electricity from the Aswan High Dam in Egypt, the construction of which submerged the original town of Wadi Halfa in 1964.

Long before the outbreak of war in Sudan on April 15, 2023, Wadi Halfa was affected by a lack of basic necessities like food and water, limited cash flow amidst a rising cost of living, electricity and internet outages, inadequate sanitation, and the spread of disease, especially during the rainy season.

The war between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has exacerbated overcrowding in the town, as people attempt to flee the conflict into Egypt, hindered by visa processing backlogs at the Egyptian consulate.

Climate change is increasingly seen as a major contributor to the conflict in Sudan, exacerbating decades of environmental challenges and fuelling social and political instability. Residents of Wadi Halfa are increasingly subject to the adverse effects of floods, fires, drought, and desertification, made worse by climate change.

Desertification and drought

Agriculture and cattle play an important role in the local economy of Wadi Halfa, along with the mining sector. There are two agricultural seasons: juruf farming, which is winter cropping after flood season, usually from November to March, and the second season from April to August, mainly known for the production of watermelon and vegetables.

The area is highly dependent on the Nile, however increasing droughts and a possible decline of the river are likely to affect the state and the country in the future, according to an ACAPS Analysis Hub report from August 25, 2023.” Since the 1970s, droughts have led people, mostly Beja communities, to shift their livelihoods from camel-rearing to breeding smaller animals and working in Port Sudan as dockers and other labourers.”

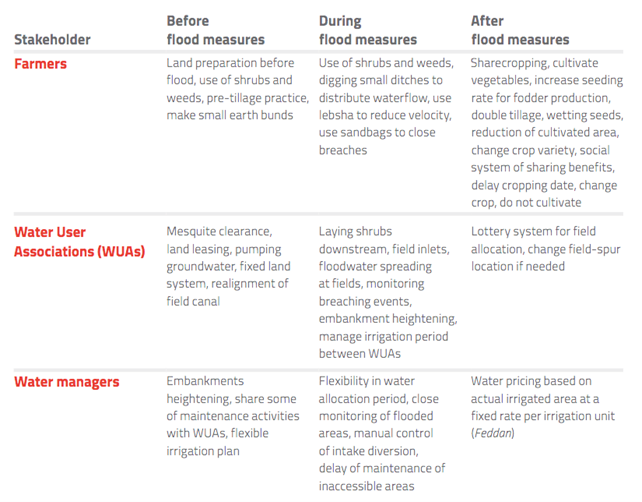

Flooding

Floods are frequent in areas within the Nile basin and low areas in the extreme south and far north. This results in the loss of crops and livestock and increases in pests, parasites, and diseases.

On August 29, Radio Dabanga reported that catastrophic floods and torrential rains had claimed at least nine lives and caused widespread destruction across the Northern State. The flood sparked a public health emergency, with outbreaks of cholera and conjunctivitis reported in several localities. Heavy rain also caused damage to houses, electric shocks, and an increase in scorpion bites. Outbreaks of cholera and other water-borne diseases can cause school and market closures, having an impact on education and the economy.

Fires

Residents of the Northern State rely heavily on palm trees, which produce dates, and thus, an income. However, many villages suffer from palm tree fires every summer, caused by high temperatures and wind. Between 1970 and 2020, droughts affected over 27 million people in Sudan, according to a report by the Sudanese Government published in 2021.

On June 23, a fire ravaged more than 1,000 date palms as well as four fruit orchards of various types in the area between Abri and Tebej, known as “Abri King” in Northern State. The fire also damaged some nearby houses and caused a prolonged power outage.

In the first half of 2024, 10 palm tree fires were reported by Radio Dabanga from Northern State. Residents continue to demand that the government provide fire engines.

International prevention

Observed annually on June 17, World Desertification and Drought Day aims to raise awareness and promote solutions to desertification, land degradation, and drought. The UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) was established in 1994 “to protect and restore our land and ensure a safer, just, and more sustainable future.”

According to the UNCCD Global Mechanism, the world needs to invest $1 billion every day from 2025 to 2030 to stop and reverse land degradation.

Restoring 150 million hectares of degraded land “could increase food security for 200 million people worldwide,” conservation agriculture could “cut crop water needs by 30 per cent during droughts,” and agroforestry and sustainable land management could “raise farmer incomes by up to 50 per cent.”

The Great Green Wall (GGW) is one such initiative of the UNCCD, introduced in July 2021 by the Sudanese Minister of Agriculture and Forests to restore and improve the condition of the land. GGW is “a comprehensive rural development initiative that aims to transform the lives of those living in the Sahel by creating a mosaic of green and productive landscapes.” In Sudan, these interventions are taking place in six states, including Northern State.

Top-down efforts

Reports of the impact of the UNCCD initiatives in Sudan are few and hard to come by, but one paragraph notes that since 2021, 1.9 million plants and seedlings were produced, 85,000 hectares of land was restored, 2,500 hectares of Assisted Natural Regeneration of forests was completed, and 1,716 residents were trained in food and energy security as well as in biodiversity maintenance.

In 2020, Sudan, then ruled by the transitional government, released its first report on the country’s environmental status and future expectations. “It presented a vision for rural development and investments to reduce rural-to-urban migration,” Abdalfattah Hamed Ali, Junior Visiting Fellow for the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, told the Arab Reform Initiative on July 24. “This report discussed, for the first time, analytical aspects and how to adapt and build resilience towards climate change. It also addressed establishing a regulatory framework for the mining sector and enhancing environmentally friendly technologies used in this sector.”

Despite these efforts, along with other national and local initiatives to ameliorate the condition of the land, Sudan often seems stuck between a rock and a hard place. National and local politics, environmental factors, the ongoing war, lack of services, and lack of citizen power all create serious barriers to substantial change.

Before the war, local initiatives against desertification focused on harnessing traditional practices for managing and preserving the local environment. “The Bashir government also introduced some policies and initiatives to combat desertification, but these efforts were weak in terms of development and research due to insufficient interest and support,” said Ali. “There was little to no coordination between the international organisations, local initiatives, and government entities.”

Future plans

In its climate fact sheet report, published June 29, the RCCC recommended a diverse array of techniques to combat desertification and drought, and improve agricultural productivity, including “maintenance of irrigation canals and pumps, improved farm machinery, credit, high-yield crop varieties, drought-resistant crop varieties, and weed and pest control.” However, any changes to rainfall are only “one part of a complex food system, and the evolution of agriculture in Sudan will also be strongly influenced by global geopolitics.”

Grassroots advocates are pressing for “defending agroecology, land rights, and territorial markets against a tide of foreign-led aid projects that erase local knowledge in favour of corporate control.” A Growing Culture, an organisation which runs communication campaigns about food sovereignty and frontline communities, reported on April 15 that across Africa, movements like Rural Women’s Assembly and We Are the Solution “represent the frontline, not just of our food system, but in reclaiming humanity’s sacred potential to imagine a better world.”

“We need to scale up ambition and investment by both governments and businesses. While the benefits of restoration far outweigh the costs, initial investments in the magnitude of billions are needed. We need to unlock new sources of finance, create decent land-based jobs and fast-track innovations while making the most of traditional knowledge,” UNCCD Executive Secretary Ibrahim Thiaw said on April 7.

Land rights protests

On June 4, protesters demanded an end to scheduled power cuts in Wadi Halfa, arguing that uninterrupted electricity from the Aswan High Dam is their basic right. They claimed that both state and central governments have encroached upon these revenues, which has marginalised the region over time.

“Wadi Halfa should be administratively separated from Northern State,” a resident said, accusing state authorities of infringing upon their rights.

They also called on authorities to complete agricultural land registration for farmer groups and allocate revenues from the region’s resources directly to local development and services. This would allow them to have power and control over electricity, water, and goods and services, making the residents more self-sufficient and able to make their own decisions about looking after their land, crops, and environment.

Protesters have vowed to continue escalating their actions “using all available options, whatever the cost, until all demands are met.” It seems that, until more power is handed over to the residents of Wadi Halfa, they do not see an end to the ongoing crises that have affected them for decades.

and then

and then