Drone strikes hit West Darfur fuel market, shelling resumes in South Kordofan as Sudan fighting intensifies

A strike on the fuel market in Adikong triggered large plumes of smoke and flames (Photo: Radio Dabanga correspondent)

Drone strikes and artillery bombardment were reported in several parts of western and southern Sudan on Thursday, as fighting between rival forces continued to threaten civilian areas and key supply routes. Witnesses said a drone launched by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF struck the Adikong market, west of El Geneina in West Darfur, near the Adré border crossing with Chad early on Thursday morning. A second drone attack was also reported on the weekly market in the area of Sileia in the same state.

Residents told Radio Dabanga that the strike on the fuel market in Adikong triggered large plumes of smoke and flames. Unconfirmed reports suggested there were casualties, while a major fire broke out across parts of the market.

The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) condemned the attack, describing it as a strike on one of the most important crossings linking Sudan with neighbouring Chad. The group said the crossing was a vital corridor for food, medicine and humanitarian supplies reaching civilians affected by the war.

In a statement seen by Radio Dabanga, the RSF called on the UN security council and international organisations to take urgent action to halt what it described as attacks on civilians and to hold those responsible accountable. Continued international silence, the group said, risked encouraging further assaults and disruption to humanitarian work.

The strike on the market was the third reported attack of its kind since the beginning of the year. It also came just one day after the Adré border crossing was reopened.

Authorities in Chad had previously closed the crossing out of concern that the conflict in Sudan could spill over into Chadian territory.

Attacks ion Salia and Abu Zabad

Elsewhere in West Darfur, sources said another drone strike targeted the weekly market in Sileia.

In neighbouring West Kordofan, Alaa Naqd, spokesperson for the Sudan Founding Alliance (Tasees), said a drone strike by the Sudanese Armed Forces on the town of Abu Zabad on Wednesday evening killed more than 20 people and wounded 23 others.

The alliance called on regional and international actors to intervene urgently in response to the attacks.

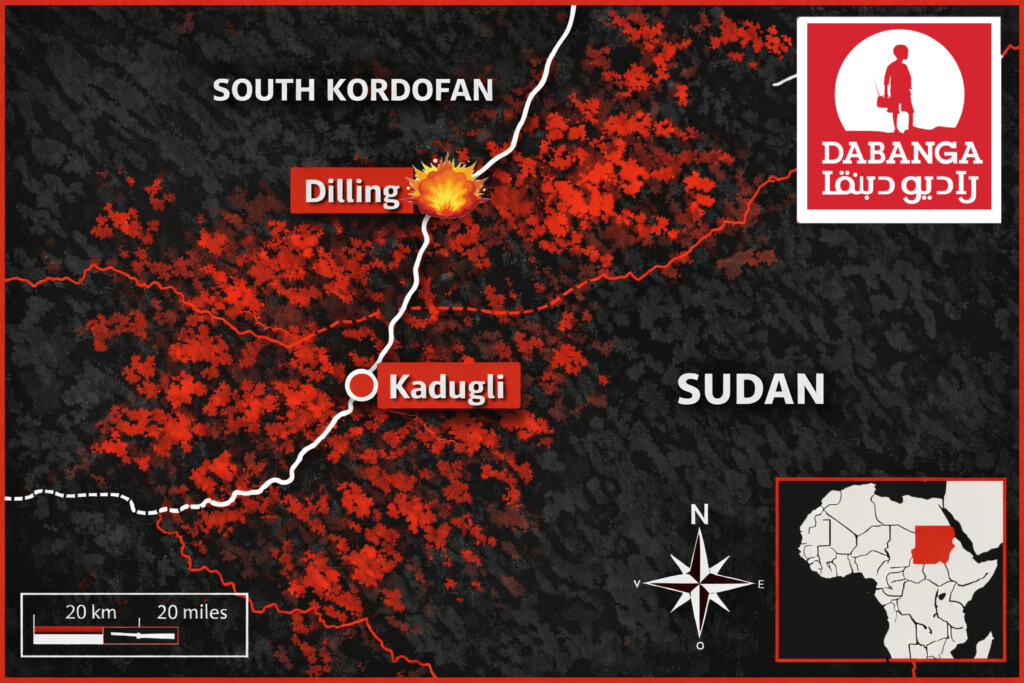

Artillery shelling on Dilling

In South Kordofan, artillery bombardment resumed on Thursday morning in the city of Dilling, with witnesses reporting that shelling from the northern outskirts of the city continued for several hours.

The bombardment was carried out by RSF forces alongside fighters from the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North led by Abdelaziz al-Hilu, according to local sources.

Separately, a recent report by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) indicated that the immediate risk of famine in Kadugli, the capital of South Kordofan, had eased, though severe hunger remains widespread in the area.

and then

and then