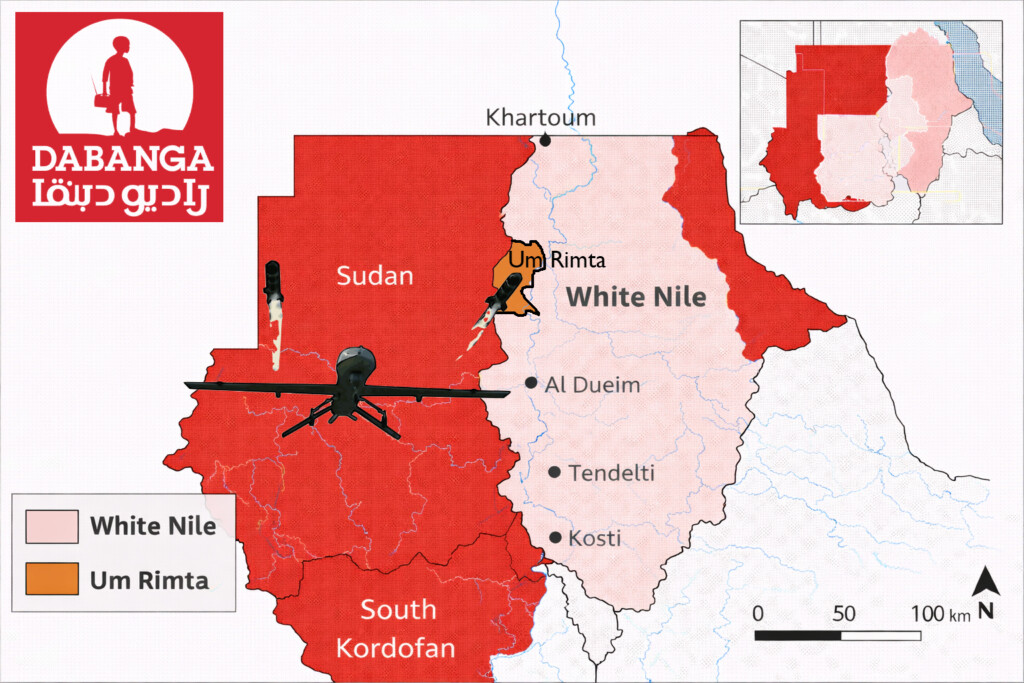

Nine dead as drone strike targets hospital, school in Sudan’s White Nile state

Map: RD

At least nine people have been killed and 17 others injured after a Rapid Support Forces (RSF) bombardment of the village of Shukairi in Um Rimta locality of White Nile state this morning, the Sudan Doctors Network confirms. Independent sources report that the attack was carried out with four suicide drones that targeted a school, a hospital, and a health centre.

The sources explained that two drones hit the Shukeiri secondary school, while the third targeted the village hospital, and the fourth hit the health centre.

The source indicated that eight high school students and a medical staff member were killed, in addition to a number of injuries among students and citizens, some of which were described as varying in severity.

The attack caused panic among the public, as well as significant damage to the school, hospital, and health centre.

The Rapid Support Forces continued their drone attacks for the fourth day in a row, as they attacked the Umm Dabakir thermal power station yesterday, which led to power outages in several cities in White Nile and North Kordofan.

The army and the Rapid Support Forces have recently intensified their drone attacks, with the army targeting large parts of Kordofan, Darfur and the Blue Nile, while the Rapid Support Forces are targeting the White Nile, the Blue Nile.

and then

and then